This is Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan.

Have You Ever Seen One?

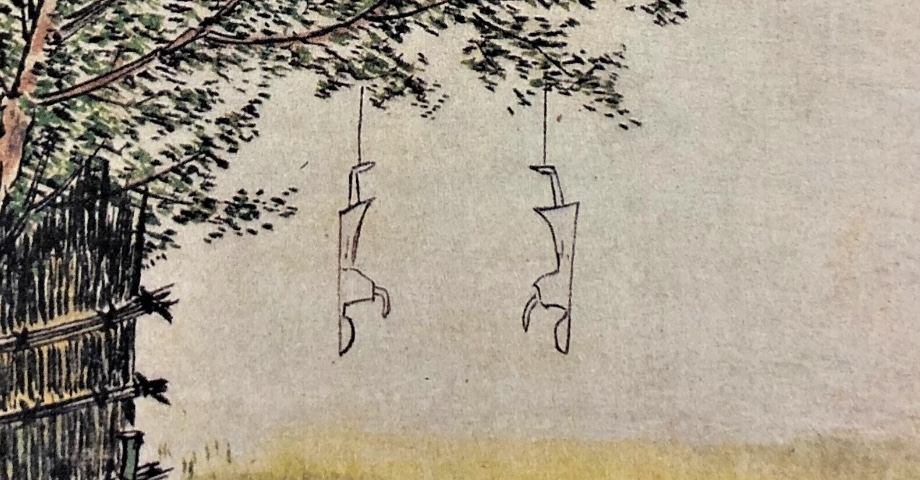

Have you ever visited Japan and went for a walk on a dark, overcast – somewhat foreboding day. And as you’re strolling down the street, you notice strung up in all the windows and under the eaves of the houses, little white ghost-looking dolls. Some have colored ribbons around their necks. Some have little smiley faces drawn on them. Some have no face at all. Isn’t it weird how the ones with eyes seem to stare at you as you walk by?

Okay, they may or may not be watching you as you pass. It’s probably your imagination. Or maybe not? Let me tell you more about this darling little talisman called the teru teru bōzu. Don’t change that dial.

Intro: Book of Japanese Folklore Preorder

Hey hey, how’s your week coming along? I hope nicely. Today I won’t harangue you except to say: The Book of Japanese Folklore: An Encyclopedia of the Spirits, Monsters, and Yōkai of Japanese Myth by Thersa Matsuura is available for preorder — hardback, kindle, and audio book which I’ll be reading — and please consider becoming a patron for extra uncanny goodness and to help support the show. Hint hint, nudge nudge. And that’s that.

The Name Teru Teru Bozu

Okay, so what ARE those ghosty-looking things dangling in windows on cloudy or rainy days? What do they do? And why do they so mysteriously appear only when it’s gloomy out?

Well first, they have a name. They’re called teru teru bozu. Teru come from the verb teru (照る) and means to “shine”. Teru Teru then means to “shine shine”. Have you ever eaten teriyaki chicken? Did you notice how shiny it was? Yup. Same kanji. Shiny grilled chicken. Anyway, bouzu (坊主) means monk, but it can also refer to someone who is bald (as monks are bald) or even a young boy, because, well, young boys used to have their heads shaven, too. So it’s completely understandable how this little good luck charm got its name. Teru teru bozu. Shine shine bald monk! Or shiny shiny bald-headed kid. Something like that.

They are also called Tere Tere Bozu, Terere Bozu, and Hiyori Bozu. They’ve been around for a while, too. In the mid Edo Era, they were used with a few differences that I’ll get into in a minute. But as for names, at that time, they were called things like: teri hina, teri hōshi, teri teri hōshi, tere tere hōshi, along with the standard teru teru bozu.

Turn Gloomy Weather Fine

Nowadays, their purpose is to turn bad weather fair or make that sun shine shine (perhaps like the glossy head of a bald monk!) They’re mostly used by kindergarten and elementary-aged children who have some sort of picnic or field trip planned for the following day, but the weather forecast looks like it’s not going to cooperate.

What’s a teacher to do? Break out the magic, that’s what. The hope is, if the entire class whips up a bunch of teru teru bōzu, then maybe they can prove that forecaster wrong. While I can honestly say, I don’t think I’ve ever known any adults who are like planning to go camping down by the river and whip one up the day before. Although they can if they want. Because teru teru bozu used to be used by adults, too. But, again, that in a second. First, how do you make one?

Like I said, to the western eye they look like little ghosts. I’ll put photos up on the Uncanny Japan website in case you’ve never seen one and a drawing on Youtube, but for now here is the step by step construction of a teru teru bozu. Just remember to make it the day before you want fine weather. Not the “day of” or a couple days before. As in all things, timing is important.

How to Make One

Your teru teru bõzu can be made of white cloth — which is the traditional way — or if you have a kindergarten class of forty kids, it might be cheaper to use tissues or as we call it in Japan “kichin pepa-”, paper towels. Keep in mind purists say using anything other than cloth lessens the teru teru power.

Here’s the easy way of doing it. It’s really easy. First wad up a couple pieces of tissue into a ball. This is the head. Then cover that with another other piece. You can use a rubber band to cinch and secure the neck, then flare out the bottom so it’s nice and ghosty-looking. Tadah!

If you want to be more traditional and have a more powerful teru teru bozu, use cloth. It has to be white cloth, but a handkerchief will do. There are a bunch of rules to follow, but if you don’t want to wad up another handkerchief for the head, a ping pong ball will work, too. Instead of a rubber band, though, use a string or ribbon tied very neatly around the neck.

Whether you use a rubber band or string, remember to take another long piece of string or thread and either loop it through the tied neck part or thread it through the top of the head, so that you can hang it up later.

To Face or Not to Face

A note of caution when drawing the face. Do you want to do this the old fashioned way or the way people are doing it now? If you’re walking around today, you’ll see most teru teru bozu with cute little smiles and red cheeks, perhaps some eyebrows and a nose. But almost always they have a face. But it didn’t used to be that way.

I’m not sure the original reason exactly, but old teru teru bozu or teri teri hōshi, didn’t have faces. One reason I found is that when you draw or paint on the face the ink will likely run and this makes the little sunshine-bringer sad and feel sad. It’s almost as if it’s crying. Then it’ll just say screw it and let it rain anyway. So you can choose. Originally, they were strung up with completely blank faces. But these days kids delight in drawing them on.

Where to Hang

Okay, you’ve got it made with or without a face — your decision. And you have a long string attached, so that you can hang it properly. Now what? Next, go and fasten it on a clothesline outside or under the eaves of your house. These days, you’ll see many dangling from windows – inside, safe from the elements – but looking outside.

Strict traditionalists say this is a no-no, and insist they should be outside to best work their magic. Also, when stringing up your teru teru-kun make sure the head isn’t drooping or looking down because that lessons its power by half. So careful there. One way you can prevent this is by using a piece of tape and taping the string to the back of its head so it doesn’t flop around.

The Song and its Meaning

You’re not done yet. Now for a little incantation. To get it to work, after it’s hanging there, you look at it and sing the Teru Teru Bozu song. I guess it’s like “Rain Rain Go Away” but with a homemade mascot.

I can’t sing, but the lyrics go like this:

Teru teru bozu, teru bozu

ashita tenki ni shite okure

itsu ka no yume no sora no yoni

haretara kane no suzu ageyo.

Which in English translate delightfully as:

Teru teru bozu, teru bozu

Make tomorrow’s weather nice for me

like the sky in a dream once upon a time

if it clears up I’ll give you a golden bell.

Isn’t that nice?

But you’re not done. Here’s another verse:

Teru teru bozu, teru bozu

ashita tenki ni shite okure

Watashi no onegai wo kiitanara

amai osake wo tanto nomimashou

The English is:

Teru Teru Bozu, Teru Bozu

Make tomorrow’s weather nice for me

If you listen to my wish

We’ll drink a lot of sweet sake

Okay. But we’re not done yet. One more and here’s where it goes dark:

Teru teru bozu, teru bozu

ashita tenki ni shite okure

soredemo kumotte naitetara

sonata no kubi wo chon to kiruzo

Teru Teru Bozu, Teru Bozu

Make tomorrow’s weather nice for me

Or if it gets cloudy and the clouds cry

I’ll chop off your head. Chon!

Ah. Japan. But I guess there are loads of lullabies and children’s songs that have a little horror in them.

For maximum rain dispelling magic, you have to sing all three verses. Even the chopping off the head one. Then, when you’re done, keep looking at your teru teru bozu and say “ashita ha tenki ga hare to narimasu yoni”. May it be sunny tomorrow.

How to Thank or Punish it

Now you go inside and wait.

The next day, if your magical buddy grants your wish and the skies clear up, you have to thank it properly. If you don’t give proper thanks, they say, don’t be surprised if some kind of bad something or other befalls you. Just sayin.

To do that, you have to take the teru teru talisman down and untie the string or ribbon from around its neck. Don’t cut it with scissors, just very gently take it off. Next, tell it thank you and if you haven’t already, draw a face on it. Make sure you draw a happy face. This also gets across your feeling of gratitude to the teru teru bozu. If it already has a face, skip this part.

While these days, I think a proper thank you and a burial in the garbage can suffices, older traditions say you should take it to a river, pour some sake on it, and float it down the river. Or the same thing but in the ocean. The idea being to give it back to nature and to purify it. I’m going out on a limb here, but I don’t think it’s super cool to be tossing things into rivers and oceans. Some say if you can’t, you can bury it in your backyard, too.

A darker line of thought says that you throw it in the river to punish it for not granting your wish. Without the sake poured all over it.

Edo Era Teru Teru Bozu

Now let’s look back a little. We know from the past couple episodes all about creating some kind of doll, be it straw or paper, or in this case cloth, and using them as vessels for divine spirits (kami). And how they acted as a kind of substitute for people, to soak up disease and bad luck or work the rice fields in a pinch. Back in the Edo Era, these teru teru bozu charms were employed more by farmers and used to pray for the cessation of rain, but because of some trip to the zoo, but to save their crops.

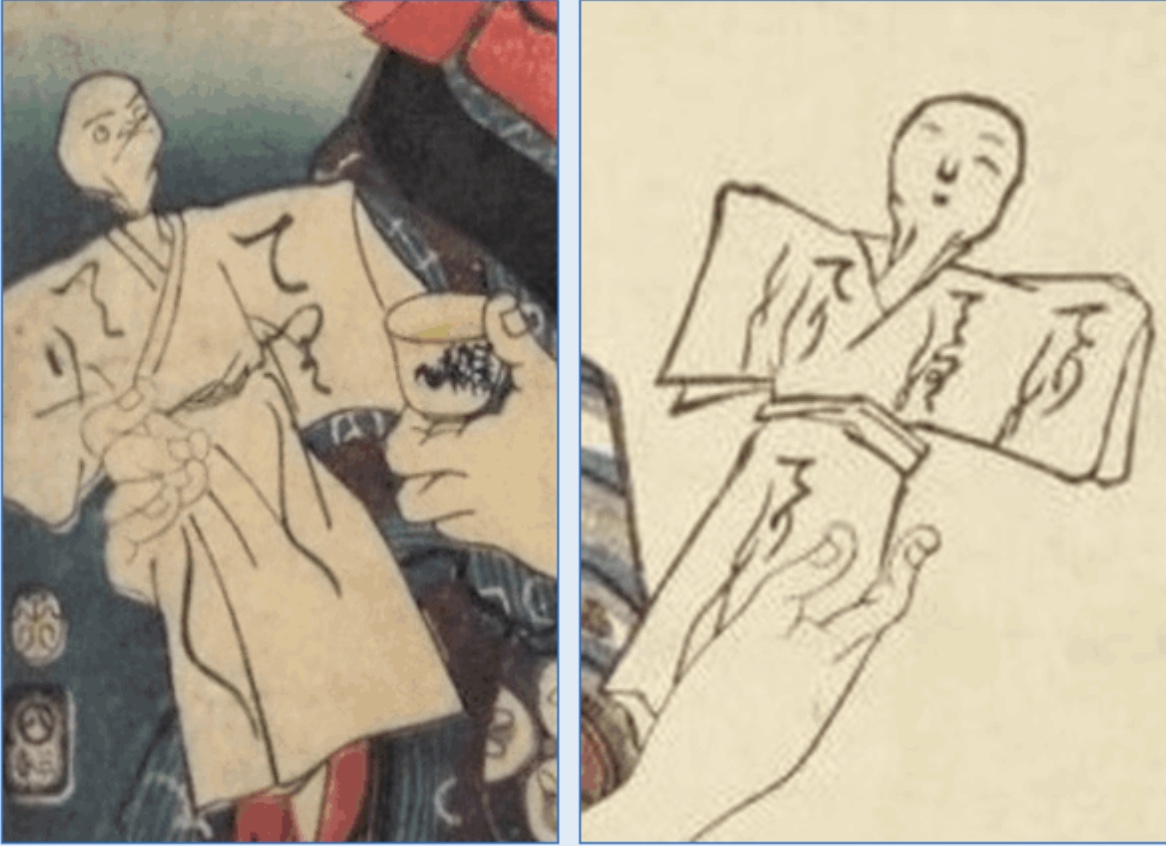

They were made of origami paper or cloth and made to more resemble a human shape. Interestingly, when offering the prayer they were cut them in half and/or hung upside down. I found some old artwork of them I’ll post on patreon and the Uncanny Japan site. Note that these days to hang one upside down is believed to invite rain.

Back then when they were done, they’d be doused with sake and of course carried down to the river to be released or if there wasn’t a river or ocean nearby, taken and left next to a pair of dosojin statues on the outskirts of town. See the dosojin episode about them.

But we can push back even further. Let’s go all the way to the Heian Era (749-1185) where it looks like something similar was going on that had been adopted from a Chinese tradition. In China instead of a bald monk dude, it was a girl with a broom which she used to sweep good luck your way. This is based on a real story about a period of incessant rain and the decision that the only way to stop it was to sacrifice a young girl, thus sending her to heaven – poor thing – to sweep the clouds away. Which she evidently did and then was prayed to there after. Perhaps this is the origin or just an older tradition that resembles the teru teru hoshi one.

So there you are. One more bit of teru teru trivia, the mascots of the city Ikeda in Nagano prefecture are based on the teru teru bozu. They’re called terumin and fuumin. And then there’s Castform, the Weather Teller Pokemon which is also based on this shiny shiny monk charm.

Thank you all for listening. I’ll talk to you again in two weeks.

My mom and I used to make these all the time! Usually we made them when we had a cold or something like that… not just out of tissues but out of cloth as well.

We aren’t Japanese at all so I’m not sure how our culture came to interpret these little dolls, I do know that my grandparents believed in the power of totems and dolls (and clearly, so did my mom!)

At any rate, thank you for this informative post! I really enjoyed learning about their history. I think whether my mom was making them for health or weather or both, she loved to make them!

We were always putting these little dolls up and taking them down. Sadly, I can’t ask her now. Maybe she is sweeping clouds ⛅️

I love when parts of one culture seemingly mysteriously get picked up by another culture. It’s like a big mystery! How did that happen? What grandmother or great grandmother heard what story from a friend…or something else. I love that you made them and carried on the tradition. And thank you so much for listening to the show. ♪(๑ᴖ◡ᴖ๑)♪