Hey, hey and Akemashite omedetō. Happy New Year. Hear that in the background? That’s what it sounds like outside my front door today. Those birds are way obnoxious, but happy it seems. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe they’re called mōzu or shrikes in English. I don’t know a lot about birds, but I’ve been told that mōzu like to skewer their meals on thorns or thin branches before they eat them. In Japanese, this is affectionately called mōzu no hayanie, or the shrike’s crucifixion, or the shrike’s sacrifice. You should also be able to hear the elderly people across the street enjoying themselves over a game of gateball too.

So, I am officially moved into my new abode. It’s old and creaky, shadowy and utterly freezing, but I love it. I have a wild masked palm civet who climbs my drain pipes at night and hangs out on the roof or in the attic, I’m not sure yet. There’s a door on the second floor that’s permanently sealed for some unknown reason. Then I have, across part of the bedroom ceiling, these mysterious dark splatter marks that evidently can’t be removed. And to top it all off, in the middle of the night when I walk down the dark, narrow hallway to go to the bathroom, the toilet greets me by making a mechanical yawning sound and lifting its lid. And then when it deems it’s time, it flushes.

I’m still neck deep in boxes though, and after stressing myself out thinking I can’t podcast again until I get everything put away into its proper place, I decided, yeah, no. And since I’ve just run across the new microphone, the binaural mics and other podcasting necessities, here I am. Surrounded by boxes, not even close to being completely moved in, but tickled pink and very much wishing you all a happy and fortuitous 2020, year of the rat.

I always want to start by real quick thanking my patrons. You are the absolute best and I really enjoy getting to know you. Everyone is so interesting and smart and so very, very nice. I wish we could all have dinner someday and maybe we could take turns crawling into the small John Malkovich door on the side of my house. The one that’s wedged shut for some unknown reason.

I also want to mention that it’s my two year anniversary of being on Patreon this January 28th. So to celebrate, I’m going to offer an Uncanny Japan sticker to all new patrons or older patrons if you’d like one. I just got an email saying they’d been mailed, so they should be here soon. So while supplies last, I can send you a two inch round sticker of the oni Ojizō character on that dark red background. It looks just like the podcast icon. And of course, $5 and up patrons will also have access to over 35 past bedtime stories, binaural soundscapes, and all the behind the curtain patron only shows. And the I just started a little while ago perk recipes. I’m planning on doing a lot more of the recipes and behind the curtain episodes this year, too.

OK, on to today’s show. Like I said, I’m not exactly on the ball. I really wanted to get this episode out at the beginning of the month. But cool New Year’s traditions are still cool, even if they’re a little late and especially if they’re about food. Now, I grew up in the south of the US, so I know about eating cornbread, collard greens, black eyed peas and pork to encourage a prosperous new year. But Japan has really outdone itself with lucky New Year’s food.

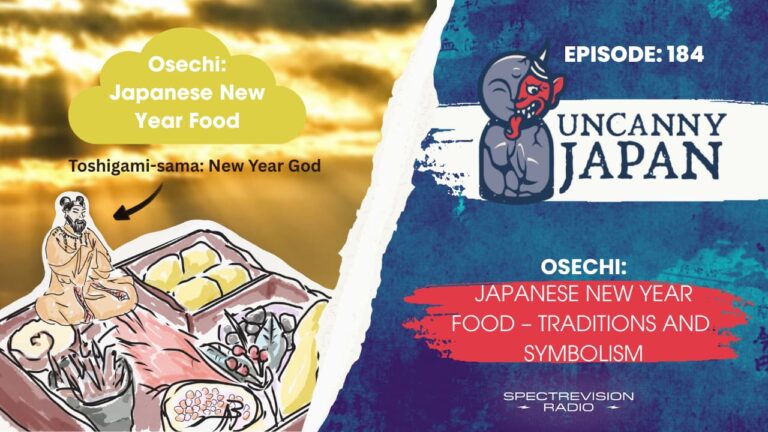

What is Osechi Ryōri?

The first thing you need to know is that New Year’s cuisine is called osechi ryōri, but I’ll call it osechi for short, because that’s pretty much what everyone does. So what is osechi? It’s a whole bunch of different dishes meticulously prepared in the days leading up to January 1st. Once finished, they’re placed very artfully into jūbako. Jūbako are these gorgeous lacquered stackable boxes. Think of bento boxes, but much more elegant and only used for serving osechi. The characters for jūbako are to stack and box, the idea being medetasa wo kasaneru, stacking up happiness. Isn’t that nice?

Now, do you remember from last year’s show, episode 13 called Teachers Running, where I talked about how at the end of the year, everyone is really busy. They’re doing ōsōji, big cleaning of all their offices and houses, decorating their front doors and entranceways, visiting friends and family and paying off debts, because if you enter the new year owing money, you’ll spend the rest of the year owing people money, or so I’ve been told. Well, they’re also busy cooking osechi.

Another thing I remember being told was that whatever you do on the first day of the new year portends what you’ll be doing for the next 365 days. If you wake up and you start washing clothes or cooking or cleaning, then that means you’re going to be doing exactly that for the rest of the year. What you want to do in Japan the first few days in January is to relax, eat delicious, auspicious food, and enjoy being around the family.

Okay, back to osechi. So, since moms and grandmoms aren’t supposed to be spending time in the kitchen those first few days of the new year, everything is prepared to not spoil for at least three days. And by not spoil, I mean, at least in my experience, not spoil while not being refrigerated either. That’s not as scary as it sounds, though. There isn’t any central heating in my part of Japan, so with the winter temperatures hovering a little above freezing, keeping the jūbako in a chilly unused room or in the foyer is usually good enough to avoid food poisoning.

In my experience, after the initial feasting on osechi, there would still be quite a bit left. So we’d set it out on a table in the genkan, the entranceway, and then when someone was feeling a little peckish, they’d go grab the stacked boxes and bring them into the heated room where we’d all nibble again. Sadly, recently I hear osechi is good for about one day and then everyone is tired of it and yearning for some sushi or pizza.

When I first came to Japan in 1990, the entire country was closed from January 1st until like the 7th. So osechi and ōzōni, a kind of vegetable and sticky rice cake soup, were all you had to eat. These days, more and more stores are open because they know everyone is itching to get out of the house, do some shopping, and eat something other than osechi. I think osechi has lost some of its glamour and respect, unfortunately.

The good thing that has happened is that these days it’s amazing how many of the dishes you can find in your local supermarkets. Little containers filled with different lucky foods. You can pick and choose, take them home, and put them in your own jūbako. You don’t even have to cook. Another really convenient tradition is that you can order osechi from these supermarkets or even konbini, convenience stores like 7-Eleven. They’re really expensive, though.

Recently, you can even find different takes on osechi, like Chinese osechi, Korean osechi, or even Western osechi. Another thing I just learned was that by not cooking during those first few days in January, you’re not only giving the ladies of the house a break, you’re also giving the furnace god, the kamado kamisama, a rest, too.

Traditional Osechi Foods and Their Meanings

Okay, now let’s talk about the kinds of goodies that make up osechi ryōri. There are quite a lot, and I’m sure they change somewhat depending on where you are in Japan, but they all have special, auspicious meanings to help you start off the new year right, and I’m sure some of the biggies can be found all up and down Japan. So here are some of the things you can find in your jūbako on January 1st and a little bit of my two cents.

Kombu or Kombumaki

I really like these, and they look cute, too. First, kombu is a thick kind of seaweed or kelp that’s been rolled into little bite-sized pieces with herring inside and tied neatly with these long, thin pieces of cooked gourd. Then they’re all simmered in a sweetened soy sauce with some dashi and ginger. Kombu is a play on words. Kombu sounds like yorokobu, which means happiness or joy.

Kuromame (Black Beans)

Another is kuromame, or black beans. These are also one of my favorites. They’re shiny, plump black beans boiled in a sugar and meaty sweetened soy sauce. Eating black beans means you’re wishing for a year where you’re healthy and strong and can mame ni hataraku, or work hard and diligently. That doesn’t sound good, but believe it or not, it’s kind of a compliment. If you live in Japan and someone tells you you’re mame, it means that you work hard and you pay attention to details, and that’s a good thing.

Kamaboko (Fish Cakes)

You’ll often hear kamaboko translated as fish cakes, but I always thought that sounded a little weird to me. They’re not sweet. Imagine a pureed fish paste that is lightly flavored. There are two batches. One is kept white while the other is dyed pink. Then the kamaboko maker uses a wooden paddle to scoop up this mixture and heap it onto a small rectangular piece of wood, smoothing it and making it like a big half circle mound, if that makes sense. The whole thing can be all white or white in the inside with a layer of pink on the outside. These are then steamed until cooked, sliced and made into a nice design in your jūbako. Usually they’re alternating pink and white. These semicircle shapes are supposed to represent the first sunrise, but also red and white are auspicious colors as well and thought to ward away evil.

Speaking of red and white, a little aside, the main TV show that is watched all over Japan on New Year’s Eve is called Kōhaku or Red and White. My father-in-law used to work in a small kamaboko factory, so we got lots and lots of kamaboko. Another thing I always liked about the end of the year is that when people are going around visiting each other, they also give each other gifts of food. For example, my father-in-law would bring home tons and tons of this kamaboko and he and my mother-in-law would drive around visiting friends and relatives passing it out. They in return would get something that maybe that family had a lot of, like cans of tuna, vegetables, sticky mochi rice cakes or even pot stickers, gyōza.

Tai (Red Sea Bream)

Okay, let’s move on. The next food you can find in your jūbako is tai or red sea bream. Again, a play on words, tai is associated with the word medetai, meaning to celebrate. Sometimes you can find yellowtail or shrimp in osechi ryōri. Shrimp is interesting because the kanji for it is ebi and that’s written as ocean old. The reason being is that a shrimp is all bent over like an elderly person’s back and the long whiskers on a shrimp look like, well, long whiskers. It’s lucky because it’s a wish for a long life.

Tatsukuri (Candied Dried Anchovies)

Then we have tatsukuri, the characters meaning literally making a field. These are candied dried anchovies. I’ve read that traditionally fish, probably dried anchovies, were used as fertilizer in rice fields and that this little sticky sweet and salty dish symbolizes wishing for an abundance of crops or wealth in the coming year.

Datemaki

Datemaki, this is another interesting food that I’m going to have to try and describe. It’s beaten eggs mixed with mushed up shrimp or white fish, flavored with mirin, a dash of soy sauce, and dashi broth, rolled up, baked, and sliced. The meaning of this one, aside from being generically good luck, is that it’s rolled up and looks like a scroll. Eating this will bring you a year of learning and knowledge. This one’s pretty yummy too and not too sweet.

Namasu

Then we have namasu. I didn’t mind this, but I had relatives who really didn’t like it because of the strong smell. It’s shredded carrot and daikon radish cooked in vinegar and sugar. Sometimes raw fish is added. It’s not exactly red and white, more orange and white, but again, it’s auspicious.

Kazunoko (Herring Roe)

Next, kazunoko or herring roe. These little yellow packages filled with eggs represent a new year of being blessed with many children or grandchildren. I was never a big fan of herring roe, even to this day, although some people really, really love it.

Kurikinton (The Favorite)

And then I’ll end with probably everyone’s favorite, kurikinton. I think it’s pretty much a given that this is most people’s favorite, at least among children. It’s kind of a dessert. What it is is chestnuts boiled, mashed, and sugared, along with some mashed up sweet potatoes. The whole thing is colored with kuchinashi, a gardenia pigment, which is a beautiful bright yellow color, making the whole thing vivid golden, and that is very lucky too. There are usually whole chestnuts left floating around in the mash, and getting them is extra lucky. By the end of the three days, pretty much everyone has picked them out, and there is nothing left but the sweet mashed potatoes.

A New Year Tradition Worth Celebrating

So those are just a few of the things that you can find in your lucky jūbako on New Year’s Day. But now, after having cooked it all, or bought or traded to get your osechi cuisine together, you also have to put them into the jūbako in a certain way, but I’m going to skip that for now, because that’s a whole ‘nother subject.

So I’ll end here, and again, I want to thank you all for listening, every single one of you, and I wish you a 2020 full of laughter and success, health, and exciting adventures. Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu. Bye bye, and I’ll talk to you soon.