On May 5th people all across Japan celebrate Children’s Day or Kodomo no Hi. It might not be a normal year, but if you look out your veranda you can possibly see some carp streamer (koi nobori). One of the ways to celebrate is with an iris bath or shoubu-yu. It’s purported to make you strong like a samurai. Another way to celebrate is for boys to set out a fancy doll. Kintaro is often found in houses all over Japan. He’s also big and strong like a samurai.

Hey hey, this is Thersa Matsuura, author of the Book of Japanese Folklore and the Coming This Fall 2025 Yōkai Oracle Deck, which you can pre-order if you’d like. I’m here to share with you all those hidden, fascinating, and sometimes frightening corners of old Japan. Come with me as I explore strange superstitions, creepy creatures, and cultural curiosities right here on Uncanny Japan.

Children’s Day vs. Boys’ Day: The Evolution of Kodomo no Hi

Looking at the calendar, I see we’re fast approaching Golden Week, the time of the year when several holidays all line up. Of all those holidays, the most exciting one is Kodomo no Hi, Children’s Day. It’s been celebrated forever, but it only became a national holiday in 1948.

The thing I find most interesting about Kodomo no Hi is that it used to be called Tango no Sekku and was celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth moon. Tango no Sekku was less Children’s Day and more Boys’ Day. You’ve probably seen koinobori, those brightly colored streamers painted like carp strung up on poles or across rivers or parks. The cloth blowing in the wind looks like a fish swimming.

In Chinese myth, a carp that swims upstream becomes a dragon and flies off to heaven. And who doesn’t want their little child to grow up and become a proverbial dragon? This isn’t set in stone because you’ll see all kinds of colors in different orders. But in general, you’ll often find the koinobori like this from the top: a big black fish for dad, a red or pink one for mom, and a blue one for the oldest son. You’ll also see green and orange wind socks for lesser siblings.

But in old Japan, the oldest son or the chōnan was pretty much the best place to be in a household. You’ll often find, usually in the genkan or foyer of a house, dolls for boys put on display in homes all across Japan. And by dolls, I mean very intricate and incredibly expensive dolls. Most of them, at least the pricey ones, will be inside a beautiful glass box. These dolls aren’t for playing with by any means.

Iris Baths (Shōbuyu): Ancient Health Ritual for Modern Families

Now on to my other favorite thing about Children’s Day, iris baths. Irises bloom during May, so of course they are a part of the tradition in celebrating your child’s health, success, and long life. Also his or her strength. Irises are fun. In Japan, they’re called shōbu. The same pronunciation with different characters also means a duel or a match, a game or a contest. Or by two other different characters, shōbu can mean martial spirit or samurai spirit.

One of the things I’ve always loved about Kodomo no Hi is something called shōbuyu or iris bath. It’s a tradition that is thought to have started back in the Heian or Nara era, but really became widespread in the Kamakura era. I heard it’s really not done much anymore, which is a shame because it’s kind of easy and it’s kind of fun.

First, irises have a strong and lovely fragrance that is thought to exercise evil spirits. So keep that in mind. Remember also that irises, shōbu, is a homonym for a duel and martial spirit. And finally, take note that the leaves of an iris are shaped like long swords. Maybe you can see where this is going.

So the idea is by taking a shōbuyu or iris bath, you’ll or more specifically your children will have a long, disease-free, healthy life and become as strong or at least spirit-wise as a samurai. Iris baths are also believed to help relax stiff shoulders and relieve back pain, offer greater blood circulation and soften your skin. Plus they smell very lovely.

How to Create Your Own Iris Bath: Step-by-Step Cultural Practice

Okay, how to make an iris bath? It’s really easy. I don’t know about anywhere else, but in Japan around Kodomo no Hi, supermarkets and florists sell bunches of iris leaves. Not the flowers, just the leaves. There’s no real special instructions. Just draw a hot bath and soak the leaves. And while they’re in there, then you get in or your kids get in, however you want to do it.

This works wonderfully with the Japanese deep ofuro. And they even have hot springs or onsen that also do special shōbuyu baths around this time. I also read that using one of the long leaves and tying it around your head or your child’s head like a hachimaki makes the whole thing more effective and more samurai-like.

So on this May 5th, Kodomo no Hi in Japanese, Children’s Day in English, wherever you are in the world, and no matter how crazy they are making you, because I’ve been there, reach over and give your kid a hug. And if you happen to have sweet-smelling irises growing in your garden, chop off those long leaves, rinse them off, and toss them into a nice hot bath. You can have a soak, or you can have your children take a bath with them, symbolically wishing for a healthy, strong, and successful life.

The Complete Kintarō Legend: Golden Boy with Supernatural Origins

The few dolls that are popular are Momotarō, the peach boy, and Kintarō, the golden boy. Kintarō is a Japanese folk hero that you can find almost everywhere. You might have seen his likeness. He’s a big chubby kid with reddish skin and a pageboy haircut with bangs. He’s also completely naked, except for a big red diamond-shaped bib with the character for gold on it, kin.

You’ll often find his image with a bear or monkeys or his trusty axe or sometimes a giant carp. All of these things and animals make appearances in the tales about Kintarō. Now, there are varying origin stories about Kintarō. First, it’s believed he was a real person, a man named Sakata Kintoki, who lived during the Heian era. Kintoki was a retainer for the samurai Minamoto no Yorimitsu and was well known for being a great warrior.

But from there, the tall tales begin. Some say he was raised by his mother, a princess named Yaegiri, in a town near Mount Ashigara. From there, he went on to befriend forest animals and just go about being super strong until he was discovered by the samurai Minamoto no Yorimitsu.

A more exciting version says that his mother fled her house and the town and her husband and moved to the forest on Mount Ashigara, where she raised her son. A version of this story has her leaving Kintarō, her son, in the wilds to die, or perhaps dying herself, thus just leaving the little boy to fend for himself. Both versions end with him being adopted by a yamauba, or a mountain witch.

Still another, and probably my favorite version of his tale, has the mountain witch being the actual mother, who got pregnant by a clap of thunder sent by a red dragon. It doesn’t sound like Kintarō had any friends of his own species. All his pals were animals, especially a big ol’ bear that he often rode around. Some tales say he could speak the animals’ languages.

He was also deft at smashing rocks to bits, felling trees with his axe, and sumo wrestling various bears to the ground. I’m not a big Kintarō fan myself. Basically, nothing opposes him or makes him interesting, except for the fact that he has a mountain witch for a mom and a big red dragon for a dad. I mean, pretty much he goes his whole life unchallenged.

Traditional Children’s Day Foods: Regional Festival Sweets

Before I talk about Kintarō, a couple other children’s day traditions that I really like. One is the sweets. It seems like with every festival or holiday in Japan, there is a special sweet that is eaten during that time. With Kodomo no Hi, it is either kashiwa mochi or chimaki.

Kashiwa mochi are sticky rice cakes filled with red bean paste or white bean paste with miso and wrapped in oak leaves. The oak leaves give them a really nice fragrance. I just learned, since it’s difficult to tell which bean paste you’re getting just by looking at the snack, the trick is that if the leaf is wrapped around the rice cake with the back of the leaf facing outward so the veins are more prominent, then there is red bean paste inside. If the smooth side or the front of the leaf is facing outward, then white bean and miso are inside.

That’s pretty cool and I’m going to test that theory next time I go to the supermarket, so I’ll let you know. Now in the Kansai or western region of Japan, oak trees don’t grow naturally, so instead of kashiwa mochi, they have chimaki. Chimaki is my favorite of the two. These are also sweet rice dumplings in different flavors that are wrapped in bamboo leaves, but their shape and the way they’re tied is fun.

They’re rolled long and thin, a little bit bigger on one end, and then they’re wrapped all snugly in the bamboo leaf with a very thin strip of what I think is part of the leaf used to wrap around and around and around and tied in this really peculiar way. It’s hard to explain, but the first time I had one, it was a real trick to open, but once you figure out how, you feel a little bit smarter.

Cultural Insights: Art, History, and Modern Celebration

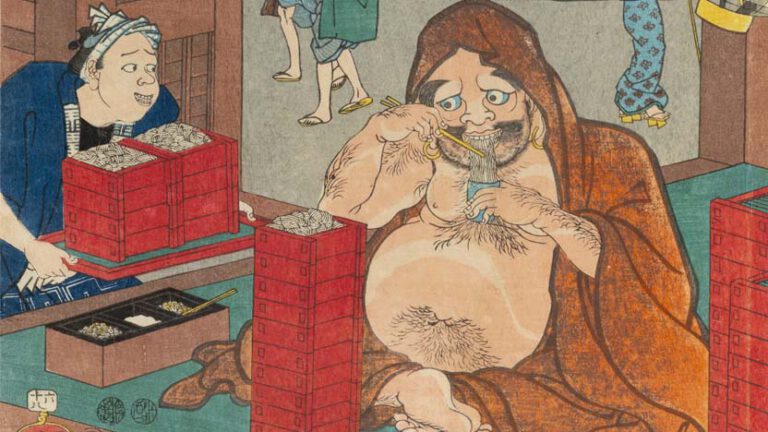

But I wanted to find some special and interesting tidbit to add here, so I did a lot of reading and I found it. Kitagawa Utamarō was an ukiyo-e artist who made a lot of pictures of Kintarō and his mother. I mean, a lot. But, at the time he was creating these images, it was the late Kansei era, 1789-1801. During that time, it was forbidden to draw, paint, or show in any way sexy women.

Now, in order to get past that decree, Utamarō got quite clever. So he would depict scenes of Kintarō, with his very non-mountain-witch-looking mother, doing mother and child things, like she’s doing his hair, feeding him soup, or cleaning his ears. That’s all innocent enough. But then you keep looking at the pictures, and there’s one where she’s sticking her tongue in his mouth, there’s quite a bit of breastfeeding and nipple tweaking, and there’s one where she’s combing her long hair with Kintarō on her back, and yeah, she’s topless.

But I guess that’s less interesting about Kintarō and more about the artist Kitagawa Utamarō, but still.

One thing all these displays have in common is that they are all symbols of strength, health and prosperity, which is again what all parents wish for their little men. Sometimes a model of a samurai’s helmet or a kabuto or a suit of armor are displayed instead.

Thank you so much for listening to Uncanny Japan. If you enjoy learning about these more elusive topics with me, I’d love to invite you into more of my Uncanny world. For exclusive content and monthly bedtime stories read by me, consider joining my Patreon community. Then there are my books. The Book of Japanese Folklore is a small, beautifully illustrated encyclopedia and deep dive into 45 yōkai and mythical figures. My horror short story collection, The Carp-Faced Boy and Other Tales, now has an audio version, also read by me and perfect to fall asleep to. And coming out in November is the Yōkai Oracle deck. 60 yōkai matched with wise Japanese idioms, phrases, and those extremely nuanced words that have no equivalent in English but you’ve always wanted to know how to say. You can pre-order those if you’d like. There’s a clickable thumbnail on the Uncanny Japan website labeled Oracle Cards. Thank you so much for listening. Stay safe and well, and I’ll talk to you again in two weeks.