Hey, hey.

My name is Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan, the place where I talk about all the more obscure, strange, and sometimes creepy parts of Japanese culture.

I’m also the author of the book of Japanese folklore and the just-released Yōkai Oracle Deck, either of which or both would make an awesome gift for your Japanophile bestie or that niece or nephew who love anime and manga and games and are just so hard to buy for, if you’re struggling to find something, that is.

There are links to those on the Uncanny Japan website or you can just order from that cool local bookstore that you love so much.

I want to thank our network, Spectrevision Radio, and remind those who would like to listen to ad-free versions of the show. They are available to kitsune patrons, $5 a month, and above over on the Uncanny Japan Patreon page.

Introduction to Oshōgatsu

So today, let’s talk about food and folklore and so many, many, many other New Year traditions. It’s one of my favorite times in Japan, and it’s coming up fast.

Oshōgatsu, the New Year.

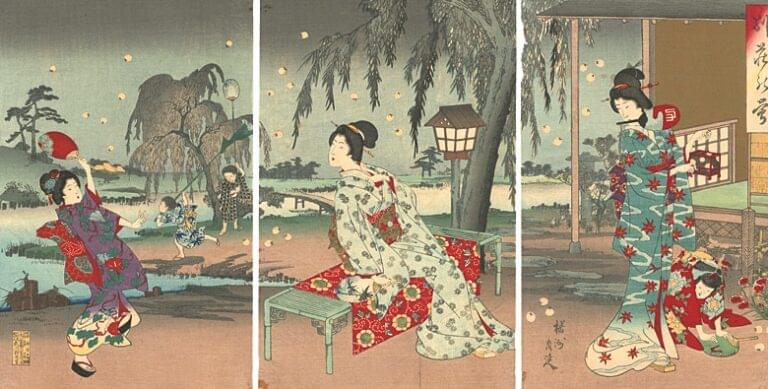

It’s when the old year is gently swept and sometimes vigorously scrubbed away, when families all over Japan travel to gather for a few days in childhood homes filled with the smells of black bean simmering in mirin-sweetened soy sauce and grilling sea bream.

And let’s not forget, it’s also the time of year the gods drop by for a visit.

A lot is going on.

One of the most interesting to me when I first came to Japan and experienced Oshōgatsu with my in-laws is osechi-ryōri.

I talked about this special, beautiful, and symbolic New Year cuisine back in episode 45. But that was a long, long time ago, so I thought I’d revisit and add some more information about the food and the holiday altogether.

Toshigami-sama: The New Year Deity

So the first thing you need to know when celebrating the New Year in Japan is, who’s it for?

It’s not just for you and your loved ones to sit around under the kotatsu, eating delicacies out of the fancy jūbako boxes, and catching up on what everyone’s been up to the last several months.

There’s actually a very, very old belief about Toshigami-sama, the god of the coming year.

This Toshigami-sama is a deity who descends from the mountains at dawn on January 1st and visits every home to bless the family with health, good harvests, and longevity.

In many rural traditions, this god is also tied to ancestors, so you have your returning family spirits and the deity of next year’s crops all wrapped up in the idea of Toshigami-sama.

And that’s why homes and businesses put out kadomatsu, pine and bamboo decorations, and hang shimenawa, fancy ropes across their entrances.

These aren’t just pretty. They’re signposts and welcome mats for this divine visitor. Please stop here. Some robust health and longevity, please.

Ōsōji: The Great Cleansing

I’ve talked about it before, but something else you’ll see in the days leading up to the last day of the year is all the cleaning, ōsōji, or big end-of-the-year cleaning.

Think of this as more than a tidying up. It’s a spiritual cleanse.

To better welcome Toshigami-sama and the new year, it’s a good idea to get rid of dust, dirt, clutter, and stagnant air. Those are all called kegare, or impurity.

And it’s not just your home, either. Before January 1st, you might want to get your car washed, get a spiffy new haircut, your nails done. I don’t know, a pedicure? But you get the picture.

People also decorate their entrances, finalize debts because you don’t want to enter the new year owing anyone any money, make visits to family and friends, and traditionally, because no one is busy enough, everyone makes, or used to make, all their new year food, osechi, by hand.

Today, things are a little different, and we’ll get to that.

San-ga-nichi: The Sacred First Three Days

So those first three days of the new year are called san-ga-nichi, and they’re sacred.

Most everything is closed, although that’s been changing recently because children are given something called otoshidama, little envelopes filled with money.

These come from their parents and relatives, and since they’re itching to buy the newest Nintendo Switch, stores are big-hearted enough to take that money as soon as possible.

Poor Toshigami-sama, not even 30 years ago. It used to be even the ATMs were closed during this time, but not anymore.

Also, there are rules for san-ga-nichi.

Traditionally, during the first three days of the new year, there should be no cooking, no using knives, no sweeping, no washing or hanging out laundry, no arguments, no crying, and no lending or borrowing.

Think of it this way. Everything you do on January 1st is a prediction of your next 365 days.

So you want calm, restful, happy times, so of course you wouldn’t want to cook.

Kamadogami Gets a Rest

There’s another layer to this, too, another reason to stay away from the kitchen.

You’re giving Kamadogami, the kitchen deity, a break.

After a whole year of tending the hearth, the stove god gets a long-deserved rest during those first few days of the new year.

Lighting fires or banging pots might disturb him and even drive Toshigami-sama away.

So what can you do during Oshōgatsu?

Eat all the pre-prepared osechi that’s served in beautiful lacquered boxes called jūbako. That’s what.

So like I said, it was all cooked before the first of the year, and it’s prepared to last for several days without refrigeration.

Think very salty, sugary, or vinegary.

It’s because the refrigerator god gets a rest, too. No, I’m kidding, actually. It’s because they didn’t have refrigeration way back then.

But since houses aren’t centrally heated, just keeping these stacked jūbako boxes out in the hall or in an unused room keeps them cool enough, usually.

I’ve had some mochi mold, although there’s a trick if you want to try it. It’s where you keep a small open container of wasabi in with the covered freshly made mochi. It’s supposed to keep them from molding.

It didn’t work for me when I tried it several years ago, or I might have just kept the mochi out way too long.

The Jūbako Boxes and Their Meaning

Okay, let’s get into the meanings behind everything.

Starting with the very elegant, stackable boxes.

Even the jūbako carry meaning. Medetasa o kasaneru. To stack up good fortune.

Traditional sets have three or four tiers, symbolizing the top box is for heaven, one down earth, below that humanity, and the bottom one, blessings, or fuku.

Classic Osechi Dishes and Their Symbolism

Let’s go over some of the classic delicacies you’ll find tucked inside your osechi boxes along with their meaning.

Konbu: Joy Wrapped Up

First, konbu or konbu maki.

Konbu, a thick kelp, is associated with yorokobu, meaning joy or happiness.

So konbu maki, little kelp rolls, often stuffed with fish, represent happiness wrapped up for the new year.

Kuromame: Black Beans for Health

Then you have your kuromame, black beans.

These glossy black beans symbolize health and diligence.

Diligence because the phrase, mame ni hataraku, basically means to work hard.

In the Edo era, the color black was believed to repel evil spirits too. So kuromame offer both stamina and protection.

And fiber. And let’s not forget a little gas to brighten up the family get together.

Kamaboko: The Sunrise Shape

Next, kamaboko.

These are usually translated as fish cakes in English, but kamaboko isn’t sweet. It’s a fish paste that is formed onto a small rectangular piece of wood and then steamed.

To eat it, you slice pieces off the wood.

Kamaboko are what my father-in-law’s company made, so we always had a lot.

They’re usually red and white, the colors of celebration and purification. Their half-circle shape resembles the first sunrise of the year too.

Tai: The Auspicious Fish

Then you have your tai, sea bream, a celebratory fish due to a pun.

Tai, the fish, and medetai, which means auspicious.

In some fishing villages, tai was offered to sea gods before the family ate it.

I’m not exactly sure why, but my in-laws never had sea bream, or at least I never got any.

Instead of sea bream, I know some people who do lobster or shrimp or crabs as their main meat of the meal.

Poor or regular people like me just have some chāshū, rolled pork, or a small chunk of ham.

Tazukuri: For Bountiful Harvests

Okay, next. You’re also likely to find tazukuri, candied anchovies, in your osechi. Not my favorite.

Literally, tazukuri means making fields. Farmers once used dried fish as fertilizer. Eating tazukuri symbolizes a bountiful harvest.

Datemaki: The Scroll of Knowledge

Another fun one is datemaki.

This too my father-in-law made, and I like it more than kamaboko.

It’s a sweet rolled kind of omelet, but not exactly an omelet. It has fish or shrimp paste mixed into it, so the consistency isn’t eggy at all.

It’s neat though, because it’s all rolled up and looks like a scroll, symbolizing knowledge and learning, and in some traditions, spiritual protection through learning.

Kōhaku Namasu: Purification Colors

Another interesting one that was never too popular in our household, kōhaku namasu, red and white vegetables in vinegar.

These colors purify and chase away misfortune, but it’s a pretty strong smell.

Kazunoko: Many Descendants

Next you have your kazunoko, herring roe.

Packed with eggs, it symbolizes many descendants and a wish for family prosperity. Not a big kazunoko fan myself.

Renkon: Clear Vision Ahead

Oh, and you can’t forget the renkon, lotus root. Here we have a winner. I love lotus root.

The holes represent insight or an unobstructed view into the future.

It can also symbolize fertility, and the lotus itself has deep meaning for Buddhists, signifying spiritual awakening and rising above adversity.

Those roots are anchored in mud, but the lotus flower emerges beautiful and clean and pure from that filthy water.

Kuri Kinton: Golden Fortune

And lastly, although there certainly can be and are other additions to osechi depending on your area in Japan and the household, let’s talk about kuri kinton, sweet potatoes and chestnuts mashed into a golden treasure.

Kinton means golden fortune. Kuri means chestnut.

This is the dish everyone loves and usually doesn’t last until day three.

Those vinegared vegetables though, they’ll still be there, day four even.

But many fights have been waged over who ate all the chestnuts from the kuri kinton.

Then and Now: Evolution of Osechi

When I first came to Japan in 1990, almost everything was closed from January 1st to about the 7th.

If you didn’t have osechi or ōzōni soup prepared, you weren’t eating.

There weren’t as many konbini back then, and I don’t remember ever seeing osechi sold in supermarkets either.

Family Traditions and Food Sharing

Once I started celebrating with my in-laws, I really liked the tradition they had, where my mother-in-law was in charge of the kamaboko and datemaki.

My father-in-law would bring back boxes full from work and the last day of the year, they’d drive around to all their friends and relatives and hand them out.

At the same time, she had a friend who grew mochi rice, so that friend and her husband would cook and pound mochi cakes and then divide those up with everyone.

My mother-in-law also had a friend that got these special black beans sent to her from somewhere in Japan, and that was her specialty, cooking those and dividing them up.

Everyone kind of had one dish they made and shared with everybody else.

By the end of the day on the 31st, everyone had their jūbako filled very nicely.

My mother-in-law always had enough to give us some, and I really had no specialty but being a mooch and occasionally making a pie, which was appreciated but had zero meaning as far as osechi goes.

Was a nice change though.

I remember one of my mother-in-law’s friends’ husband worked canning tuna, so they’d bring over a big box filled with cans of tuna fish.

Didn’t feel very osechi, but hey, neither is pie, and it was very welcome on day three or four when everyone was pretty sick of picking over the dregs of osechi.

Modern Convenience Culture

That was then. Nowadays though, supermarkets sell tons of small containers or packages of each different item, and you can pretty much pick and choose what you like or how much you like, or a lot of people I know prefer to order their osechi from somewhere and have it delivered or pick it up.

Department stores, supermarkets, even 7-Elevens all have brochures that you can peruse and choose your favorite type of osechi. Expensive though.

My brother-in-law just told me that he likes to use his credit card points to order his. Talk about convenience culture.

There are even non-Japanese osechi sets. You can find Chinese, French, Korean, and Western-style osechi.

Not sure what happens to the meaning when you get those though.

There are one-person osechi sets for people living alone, anime-themed osechi with Pokémon or Demon Slayer jūbako, and of course, the super high-end osechi, costing thousands of dollars.

The heart of it hasn’t changed so much. Even store-bought osechi still welcomes Toshigami-sama, honors the ancestors, and marks a sacred pause between the old year and the new.

Otoso: New Year Sake

Let’s talk about drinks.

Another specialty during the New Year is otoso, spiced New Year sake.

This is a medicinal herbal sake that is believed to drive out sickness and evil spirits.

Families drink from tiny cups or choko in a specific order, either youngest to oldest or vice versa, depending on your region.

Our family just went for a regular bottle of sake, one with gold flakes in it, and no real order. Just drank it first thing in the morning too. That was always weird to me.

Ōzōni: Mochi Soup Traditions

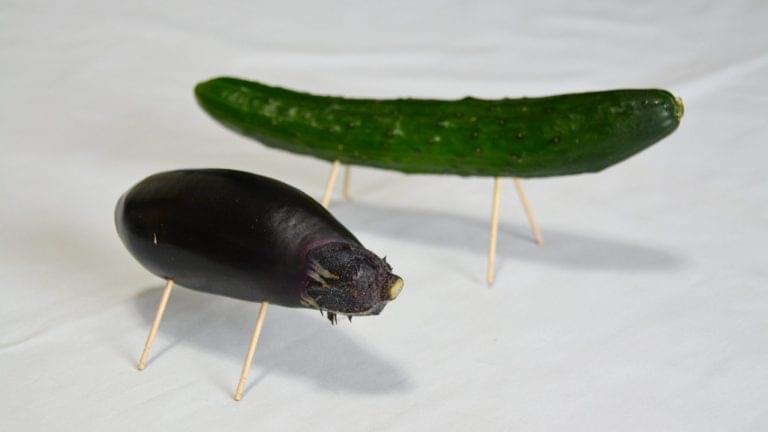

Another important meal you’ll enjoy during the New Year is ōzōni.

It’s a kind of mochi soup with veggies and sometimes meat, like small pieces of chicken or fish.

This tradition is also ancient, and in some regions, this ōzōni was originally the offering to Toshigami-sama before humans ate it.

Every region does ōzōni differently, it’s hard to narrow it down because it feels like kind of every family does it differently too.

But very generally, in Kyōto and Western Japan, Kansai, you’ll find white miso soup with round mochi and lots of veggies.

Kantō, Eastern Japan, does a clear soy sauce-based broth and square mochi and lots of veggies.

Some boil the mochi until it’s soft in the soup, others grill it so that it puffs up and then they plop that in there. I like the grilled kind.

You’ll also see carrots, satoimo potatoes, shiitake, narutomaki, kamaboko, all kinds of greens, and even sweet azuki beans are used.

Mochi: The Spirit-Filled Food

Speaking of mochi, let’s talk about that glutinous rice that when pounded becomes thick and sticky and utterly delicious when eaten just about any way you want.

But be careful, it’s very sticky and very hot, and invariably, with people all across Japan eating it, accidentally some people choke on it, some people die.

Mochi is deep.

It appears in the Yayoi era, 300 BCE to 300 CE, in agricultural rituals.

Also it was used in ancient Shinto offerings, Heian court ceremonies, and samurai traditions.

Think of it as a spirit-filled food. Why? Because rice is life.

Rice is the body of the harvest deity and the soul of the ancestors. Or something like that.

There are mochi-pounding ceremonies and events all over Japan at the end of the year.

An auspicious day is chosen, the giant mortar and pestle are taken out, and everyone gathers to help pound the rice into sticky deliciousness, and then divide it up, share it, or eat it right there.

Kagami Mochi: The Mirror Offering

But do you know kagami mochi, or mirror mochi?

Kagami mochi is taken and shaped into two round cakes, which are then stacked on top of one another, with a daidai, bitter orange, placed on top.

The shapes resemble mirrors, which you see in Shinto rites a lot, as symbols of purity, reflection, and truth.

You’ll remember the goddess Amaterasu was lured from her cave using a mirror, so they’re very important.

They also symbolize light returning, which is a great theme for the new year.

Side note, the bitter orange, the daidai, means generation after generation. So prosperity and long life, generation after generation.

A small shimenawa rope is sometimes tied around the mochi to mark that this mochi is sacred territory. There is a god in there. Don’t touch it, and don’t eat it. Not yet, anyway.

Kagami Biraki: Opening the Mirror

All over Japan, clubs, teams, and community groups prepare this kagami mochi.

Then at the beginning of the year, usually around January 11th, but sometimes earlier, sometimes later, everyone gets together to do kagami biraki, or opening the mirror.

This actually comes from an old samurai ritual, where clans would get together to break open their ceremonial mochi, or sake cask, and pray for victory in battle, unity of the clan, and strong bodies and spirits.

This is why you almost always see martial arts schools continuing the tradition.

Kendō, jūdō, karate, aikidō, kyūdō, always do kagami biraki, usually alongside the first practice of the new year, hatsukeiko.

After breaking the mochi, everyone eats it in either ōzōni soup or oshiruko, sweet red bean soup, again with wishes for unity, renewal, physical strength, cleansing, good luck, all that.

Closing Thoughts

So whether your osechi is lovingly handmade, bought from 7-Eleven, or a mix of both, the meaning remains.

Start the new year with beauty, intention, calmness, and a little bit of God magic.

Okay, I’ll stop here for today.

Thank you so much for listening and supporting the show this past year. Thank you patrons, especially because you guys really make it worth it, as does Spectrevision Radio.

We’re going away for the holidays, so the next episode of the show will be in the new year, 2026, the year of the horse.

So everybody, please have a safe and warm or cool, peaceful end of the year, and beginning of 2026.

I will talk to you all again real soon. Bye bye.