You’re not gonna believe this, but you have not one, not two, but three worms or parasites writhing around in your body right now, actively trying to kill you, but not in the way you think.

Oh, did I say worms?

I meant corpses.

Hey, hey, I’m Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan. I’m the author of the book of Japanese folklore and coming soon, the Yōkai Oracle Deck.

The deck is 60 yōkai, beautifully illustrated by Michelle Wong, that I paired with 60 wise Japanese sayings. These are phrases and idioms that I’ve collected and fell in love with over the years, and they eerily and perfectly fit with the spirit of the yōkai I paired them with.

So it’s an Oracle Deck with wise advice, but also great for Japanese language learners. Think of all those words and phrases in Japanese that we don’t have translations for in English. So 60 of those, and I explain their nuanced meanings too. Let’s move on from tsundoku and kintsugi. You can pre-order anywhere you’d like, and pre-orders are hugely helpful for a writer like me.

So the Yōkai Oracle Deck by Thersa Matsuura. And remember, there are ad-free versions of this show up on the Uncanny Japan Patreon page for kitsune tier and above. That’s along with all sorts of other content. Handmade postcards, bedtime stories read by me, Japanese soundscapes, recipes, etc.

Alrighty then, let’s talk about body worms.

Discovering Kōshintō: The Mysterious Stone Monuments of Rural Japan

I finally got to go on a walk again. All of August has just been too hot. I still can’t go outside anywhere near noon, because even though it’s September in Japan, we’re still having danger zone and heat stroke alerts, almost daily.

So it’s a good thing that I’m awake around 3 or 4 AM, and sometimes step outside to check on the moon and the night sky, see what they’re up to. Because when I did that the other day, it was a wee bit nice outside. Clean weather.

I guess you have to picture this. I live around rice fields, mostly. There are some houses, of course, along the main road that leads to the 7-Eleven and a micro-grocer that sells meat that I strongly encourage you to sniff before you buy. And they don’t sell cumin or cream cheese, because they’re too exotic.

So rice fields alongside a modest river, a handful of houses and greenhouses here and there, and then every so often, a knee-high stone tower or stele. These are called kōshintō.

Some of them look like gravestones, all roughly hewn, cracked and moss-covered. Others look like a slice of rock sunk into the earth. The ones around here are all well taken care of. There’s a vase or two with flowers, fresh or plastic. Occasionally, other offerings.

They’re swept and neat because some sweet person living nearby tins them because they want to. Or the local neighborhood group makes sure that they’re tidy. They kind of look like they just popped up at these random locations, but that’s not the case. The house, the road, the small mom and pop shop were all built around these small monuments. Those kōshintō have been there for centuries. And they’re not graves, either. They’re small monuments called zuka.

Some have faint engravings saying “kōshin,” “kōshintō,” or “kōshinzuka.” Some have beastly-looking mini-armed figures carved on them, and maybe a monkey or three, or a rooster. I’ll get to what those are about in a minute.

The Kōshin Faith: Understanding Japan’s Ancient Spiritual Parasite Problem

But let’s talk about the three-body parasite problem. I briefly talked about this topic eight years ago on one of the first shows, but I’ve always wanted to revisit it. So here we are.

Kōshin, or kōshin shinkō, the kōshin faith, and more specifically, sanshi. Those are the bad guys.

First, let’s start with that outlandish statement I made, that we, all of us living people, have three worms or parasites inside us right now, and they’re up to no good. We do, and we didn’t even have to eat roadkill to get them. That’s because these are more spiritual worms, not literal ones. But they’re just as dangerous, if not more.

The idea comes from an old Taoist folk belief, called kōshin in Japanese, or kōshin shinkō. While it originated in China, it found its way to Japan, and after arriving here, was influenced by Japanese Buddhism and Shinto, and then kind of became its own thing.

The basic belief is that there is something called sanshi that reside in all humans. San, meaning three, and shi is the character for corpse, or dead body. But actually, in this case, it’s better to think of it as meaning a spiritual parasite.

Real quick, other words for these three pests are sanchū, literally three bugs, but also sanho or shiho.

The Three Sanshi: Meet Your Spiritual Parasites

So these sanshi are with you from the moment you’re born until the day you die, and their sole purpose is to make you sick, shorten your life, and eventually kill you.

In the 4th century, there was a Taoist monk named Ge Hong who wrote a text called “The Master Who Embraces Simplicity.” In it, he said that these sanshi are in fact kishin, or demon gods. He wrote that they have no physical form, so they just roam around inside your entire body your whole life.

Eventually they were more creatively imagined and named. So there are three types of sanshi, the jōshi, upper corpse worm, the chūshi, middle corpse worm, and the geshi, lower corpse worm. They’re said to be ni sun, or 6 cm, or 2.4 inches long or tall.

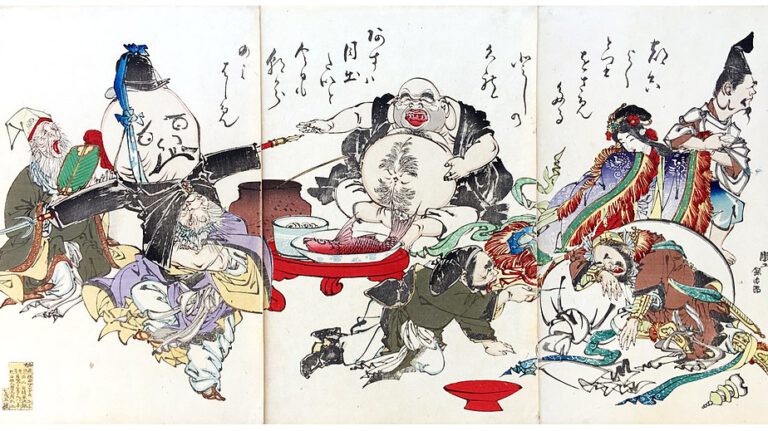

And while some texts say that they look like a small child or a horse, there’s a famous depiction that you’ll almost always see when researching the sanshi. I love it so much I’m going to describe it.

The jōshi, upper worm, looks just like an old Taoist sage, robes, nice mustache, holding a scroll in his hands. He resides in your brain and does things like instigate gluttony. Any kind of trouble you have above the neck, headaches, eye strain, madness, that’s the doing of the jōshi. Its color is blue or black.

The chūshi, middle worm, looks like a shishi dog or shīsā in Okinawa, but when written it just says that it looks like a beast. Its color is white, blue, or yellow. It’s got its scroll gripped firmly in its mouth. This one hangs out in your belly and likes to make you desire money and material things. If you have any middle body problems, stomach ailments, or even organ failure, that’s the chūshi’s doing.

The geshi, or bottom worm, is the adorable one. It looks like a single leg with an ox’s head on top. It too has a rolled up scroll in its maw, and it can be found in one or the other of your legs or feet. All diseases from the waist down are because of its shenanigans. Illnesses it causes are aches and pains of the legs, paralysis, and it also makes you lust.

How the Sanshi Work: The Heavenly Reporting System

So why do they want to see us deceased? Because while we’re alive, they are mostly trapped inside us. Once we die, they are freed, and once free, they can go anywhere they want, and if they’re lucky, can find someone to worship them. I read too that their motivation isn’t so much freedom, but a kind of evolution. They level up once outside the human body.

The kōshin belief entered Japan in the Heian era and was adopted by the aristocracy, and it became a bit of a big deal. From there, during the Muromachi era, the samurai started getting on board. Until the Edo era, when it spread down to the common folk, and it really took off.

Okay, other than making you ill, how else do these three spiritual worms try to actively cause your demise? Well, the story goes that every 60 days, on the day of the monkey, they wait until you fall asleep. That’s when they’re allowed to escape your body. Yes, they can, but only for one night.

Each one grabs its scroll in its hands or mouths and zooms on up to heaven, where the heavenly emperor or director of deeds, Tentei, is waiting. There, the sanshi take turns reading off everything you have done wrong in the past 60 days. Every misstep, misdeed, and sin. Then they argue that you should be punished.

For a small infraction, your life is shortened by three days. Something bigger? 300 days.

The Solution: Kōshin-machi All-Night Vigils

So what can you do about this three-body parasite problem? Well, for one, you can be a really good person. But that’s not always possible. I mean, we are just human, and we sometimes lose our temper or eat too much ice cream.

People back in the day came up with another simple and clever solution to this predicament. If the sanshi can only leave your body when you sleep, then don’t sleep. Stay awake all night long and trap those buggers inside you.

This practice is called kōshin-machi, or kōshin waiting. Since doing this alone isn’t very fun, and seriously, just staying awake all night can be difficult if you’re a regular person who has been out plowing fields all day long, people reached out to their neighbors and made a little event of it, like a get-together or a party.

This is called kōshinkō, and when I say party, yeah, kind of a party. When you’re spending all night long hanging out with your friends, and of course there’s going to be food and drink, which is ironic because the sanshi, also called the three death bringers, are locked inside you and witnessing all this, furiously scribbling all your antics down, but they can’t break free to go and tattle on you because you won’t sleep.

Remember those little monuments I mentioned? In some areas, after a group, a kōshinkō, continued for three years, they would erect one. There are different reasons, but it was a thing to do to build these little monuments for kōshin.

The Extreme Approach: Taoist Methods for Eliminating Sanshi

So one way to prevent your life being shortened by the sanshi is just to be a very good, sinless person. A second and more fun way is to hang out with your friends every sixty days, eating and drinking and definitely not sleeping.

Most people stopped there, but the Taoist sages back in China, who were on a quest to attain immortality a lot of the time, were a little more hardcore and didn’t do things the easy way.

By fasting, they would starve the upper worm. Remember the one in your brain that caused gluttony? Meditation and practicing detachment would starve the middle buddy, as he loves greed and materialism. Finally, celibacy would starve the lower leg-shaped parasite, who’s all about lust.

This didn’t happen once in a sixty-day cycle, though. It took many, many years. You’re making yourself a pure human being, your body a sacred place, and you weaken the sanshi in the process. Then, they believed once weakened, they could be quashed by taking a special potion that contained cinnabar, mercury sulfide, which actually causes a long and painful death. So don’t do that.

The Mystery of Cinnabar: Understanding Ancient Alchemy

I’m a little excited that I think I found the answer I’ve been looking for since I was in high school. Why did the Taoist sages have such an obsession with cinnabar? Why ingest this obvious poison? Here’s what I found.

Cinnabar is a heavy, reddish-colored rock that, when heated under the right conditions, performs a miracle. It produces quicksilver, or liquid mercury. To these ancients, this would look like a dead rock turning into a living, flowing, beautiful, silvery metal. This could then be combined with sulfur, and it would transform back into red cinnabar.

The whole process must have looked like true magic. A rock to a liquid and back again. A dead thing into a living thing and back again. And so, perhaps it was thought to hold the secret to overcoming death.

Anyway, a lot of people, sages and Chinese emperors alike, historically died horrific deaths by consuming this elixir. So they started out with the right idea, fasting, meditating, working to make their bodies and minds more holy. They should have stopped there.

Heck, just by doing that, they were probably starving the sanshi of sins to report to heaven anyway, which would in effect lengthen their lives.

The Protector Deities: Guardians Against the Sanshi

Now we know there are three worms that are dead set on causing us harm. But there are also three deities who are here to protect us. You can sometimes see their images depicted in kōshin art and on stone monuments.

The first and most prominent would be a fierce deity named Shōmen Kongō, Blue-Faced Vajrapani. His powers are healing against various diseases and protecting you from demons. Basically, any ailment that you might get because of some demon or oni, he’s there to help. He’s angry, he’s blue, and he has anywhere from four to eight arms. You’ll also find him standing on top of a couple pathetic-looking creatures. Those are jaki. Jaki are small evil dudes who you’ll often find being stepped on in Buddhist artwork.

The second guardian is Sarutahiko. He was introduced from the Shinto tradition. Sarutahiko looks quite like a tengu with its red face and long nose. It’s the Shinto deity of crossroads.

And then there’s Taishakuten, originally the Hindu god Indra. He also became a protector deity in Buddhism.

So while you’re having your kōshin-machi, waiting during the kōshin, it’s a good idea to have a scroll or a statue of one of the above deities in the room, just for further protection.

Identifying Kōshin Art: Visual Elements and Symbols

A couple things you might look for to identify whether or not the piece of art is a kōshin one or not. You might see a sun and a moon on it up top. This indicates the night and day, staying up all night until the next morning.

There are sometimes chickens or a rooster. What wakes up with the sunrise besides me? Chickens and roosters do. There are often two to four grisly-looking demons or intense warriors hanging out. A couple human-looking attendants, dressed nicely. And then something called a shōkera.

Shōkera is shown differently, but think of it as a beastly little monster whose job it is to punish evil. Sometimes it’s literally gripped in the left hand of Shōmen Kongō. It goes around, and if it finds someone asleep, it allows the sanshi to escape and make their way to heaven. So it’s probably good that Shōmen Kongō has a tight hold of it.

The Three Wise Monkeys: A Spiritual Defense System

Note, in kōshin, the shin character actually means monkey. And remember the sanshi leave your body on the day of the monkey. So lots of monkey going around. Very interesting. Are the three wise monkeys, see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil?

Well in Japanese they’re iwazaru, kikazaru, and mizaru. I did a whole show on them in episode 70, but a quick recap. The Japanese version doesn’t have evil in the name. It’s more see not, say not, hear not. And it’s also a play on words.

Saru means to expel or drive out or drive off. But the same pronunciation with a different kanji means monkey, saru. So by invoking, for lack of a better word, the three monkeys, perhaps they pass their traits along to the three parasites.

So now if and when the sanshi do flee your body to report your misdeeds up in heaven, they didn’t see anything, didn’t hear anything, and certainly can’t say anything. So you’re safe. Phew.

Modern Applications: Japanese Language and Cultural Expressions

Okay, now you know about the three deadly spiritual parasites who are right at this moment writing down every evil deed you’re doing, every evil thought you’re thinking. And you know you can either straighten up and fly right, or just stay up all night and keep them trapped inside your body every 60 days for the rest of your life.

The next kōshin-machi, by the way, is October 18th, and then after that, December 17th. I’m totally not encouraging this. It’s more of a for educational purposes only. I don’t want any phone calls from any bosses or teachers. I’m a believer in a good night’s sleep.

Okay, let’s end on something fun. Language. The Sanshi are three worms or bugs that dwell inside you, right? Well, there are quite a few sayings in Japanese that reference them, calling them “mushi” or “bug.” And if you didn’t know that’s what the saying is referencing, you’d be a little confused. But now that you do know the background, it’ll be easier to remember and impress your friends by using the sayings in casual conversation.

Let’s just do a couple. The easy one, “mushi ga ii,” literally, “the bug is good.” This isn’t a good meaning though. Remember, the bugs are bad. So when those bugs or worms or parasites are in a good mood, it’s actually a bad thing. In this case, it could be someone who is self-centered or selfish, or they have a lot of nerve. Taking someone or something for granted, or doing something convenient only for oneself.

A level up is “mushi ga yosugiru,” “the bug is too good.” Again, someone being too selfish. They’re only thinking about themselves without any consideration for anyone else.

Another one I feel is common and that I like is “i no mushi no idokoro ga warui.” I think this one is really cute too. The literal meaning is, “the location of the bug in my stomach is bad.” And it means to be in a bad mood or cranky or irritable for no apparent reason.

Okay, one last one. “hara no mushi ga osamaranai,” “the bug in my belly won’t calm down.” In this case, you’re seething with anger.

Okay, we’ll end here for today. Everyone please take care, keep those spiritual worms in check, and I’ll talk to you again in two weeks. Bye-bye.