Another Chilling Children’s Song (Episode 104)

I’m Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan.

Difference Between Kagome Kagome and Toryanse

Do you remember when I talked about Kagome Kagome back in episode 53? A Japanese children’s song that had curiously unnerving lyrics about a bird in a cage (“Oh when will it be let out?”). And then the lines: “Tsuru to Kame ga subetta – the crane and the turtle slipped”; and “Ushiro no shoumen dare? – Who’s behind me?”)

Guess what? That’s not the only goosebump-raising children’s song in Japan. There’s another. Well, at least one more.

Today I’m going to tell you about the song “Toriyanse.” Like Kagome Kagome even Japanese people have a very off vibe from the lyrics. Something feels wrong about them, what are they alluding to?

As for the game played with the song:

While “Kagome Kagome” was played like blind man’s bluff, where you blindfold one child and the others walk around them, singing. When the song stops at “Ushiro no shoumen dare? Who’s behind me or you?” Then the blindfolded player has to guess who’s standing behind them.

“Toriyanse”, on the other hand, is played like “London Bridge”, where two children are ‘it’, or ‘oni’ in Japanese. They hold hands, raising them like a arch and the other children file underneath while everyone sings. On the last line the hands come down and catch the chosen child. And I read at least one version that said, if you are caught something unlucky will happen to you.

What kind of song is “Toriyanse” and why does it freak out so many people? Well, let’s find out.

Into:

Hey hey, let’s talk about another strange children’s song that came about and was popular during the Edo Era (1600s until mid 1800s). It’s called Toriyanse and if you live in or have been to Japan, you might have heard it before. In a very unusual place. But I’ll get to that in a minute.

Lyrics in Japanese

First, the lyrics. They’re interesting in that they’re written as a conversation between two people, generally believed to be a mother who is traveling with her child and a monban / 門番. A monban is a person who guards a gate. In this case, one of the gates that lead into the castle grounds. So the song is the mother and the guard talking back and forth.

In Japanese, it goes something like this:

Toryanse, Toryanse / 通りやんせ 通りやんせ

Koko ha doko no hosomichi ja? / ここはどこの細道じゃ?

Tenjin sama no hosomichi ja / 天神様の細道じゃ

Chitto toshite kudashanse / ちっと通してくだしゃんせ

Go yo no Nai mono toshasenu / 御用のないもの通しゃせぬ

Kono ko no nanatsu no oiwai ni / このこの7つのお祝いに

Ofuda wo osame ni mairimasu / お札を納めに参ります

Iki wa yoi yoi, kaeri wa kowai / 息は良い良い帰りは怖い

Kowai Nagara mo / 怖いながらも

Toryanse, toryanse / 通りやんせ

Lyrics in English

Then a rough English translation:

Pass through, pass through

Where does this narrow path here lead?

This is the narrow path of the Tenjin God’s Shrine

Please allow me to go through for a bit

Those without good reason shall not pass

To celebrate this child’s seventh birthday

I’ve come to give my offering — (more on this in a second)

Going is fine, fine, but returning will be scary

It’s scary, but

Pass through, pass through

As always let me preface this with there are several different interpretations and beliefs about the song and its lyrics and what it means. I’ll try to talk about the major ones here and about a line that I am sure is translated wrong everywhere. I actually asked several friends to make sure I was correct. And it seems I was.

Detailed Breakdown of Lyrics

Let’s go line by line:

First, we have our guard man or gatekeeper, our monban saying:

Toryanse, toryanse. Touru / 通る means to pass through a place, but what’s this yanse business? Well, back in the Edo Period using ‘shansu’ or ‘yashansu’ like this was a polite and respectful suffix to your verb. I found a Japanese folk song website that said ‘toryanse’ is probably a shortened version of “douzo otorikudasai” which nowadays would be “douzo otorikudasai” or in English: please pass by or please pass through.

Next, is the mother’s line. She says:

Koko ha doko no hosomichi ja? It means something like where does this narrow path lead or more literally what is this narrow path?

In reply the guard who we can imagine now is guarding a narrow path not a big gate, says: Tenjin sama no hosomichi ja. It’s Tenjin sama’s narrow path.

Tenjin sama is the patron god of academics and learning. Sugawara no Michizane (also know as Tenjin) was a real life scholar, poet and high level administrator during the Heian Era. Back in the 800s. He was so incredible and respected that through time he kind of transformed into a god. I imagine like how saints become saints.

It seems that there are two shrines this song could be about.

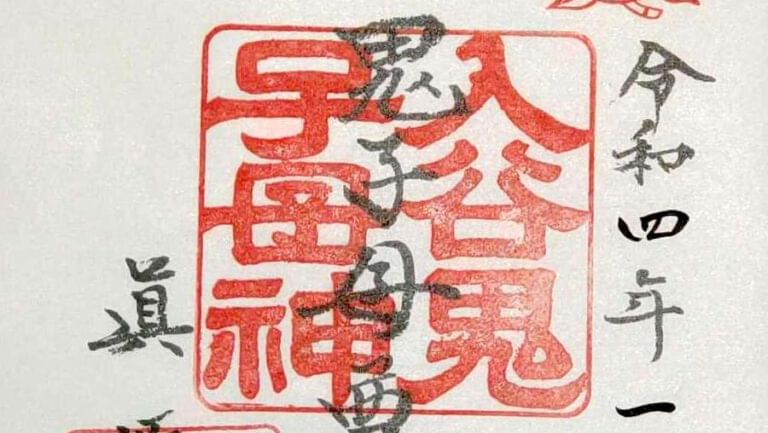

Number one: Miyonoshino Shrine in Kawagoe, Saitama Prefecture is the one I saw mentioned most. This shrine is also known as Oshiro no Tenjin Sama, The Tenjin of the Castle. So the Tenjin-sama in the song probably refers to this shrine. As proof, if you go to this day you’ll find a stone monument dedicated to this children’s chant.

The second possibility is Sugawara Jinja in Kanagawa prefecture Odawara city. This one seems to match only because to get to it you have to pass a long and narrow and at the time surely treacherous road to get to it. At the end of the song when it says going is easy but coming back will be scary, some think they’re talking about returning in the dark along this dangerous road.

Either way the story goes the shrine was on castle grounds and during the Edo Era and regular folk just couldn’t wander in whenever they pleased.

Hence the monban / guard man.

Next lyric, the mother sings: Chitto toshite kudashanse

Chitto means a little, just a bit. Toshite kudashanse. Now you’d say something like Toushite kudasai. But remember shanse was that lovely sounding way to be polite. Please let me pass.

The guard replies with: Go yo no nai mono toshasenu

Go yo means some kind of business, important business most likely. Go yo nai mono, those without business toshasenu, won’t be allowed to pass.

So at first the guard is like, pass by pass by, now he’s changing his mind.

Mother comes back with, Kono ko no nanatsu no oiwai ni. Kono ko no, this child’s Nanatsu no oiwai, seventh celebration, or birthday. The child is in their seventh year.

It’s my child’s birthday, let me through. Visiting shrines on birthdays and special occasions was not uncommon at all, even these days. The 7th year is an important one, so that’s most likely why they’re making the trek to the Tenjin Shrine inside the castle grounds.

Maybe you know about the tradition of Shichi-Go-San (7-5-3 celebrated when a child reaches each of these ages. Especially during these three years parents would (and still do) take their children to the shrine to thank the gods for all the fortune and health and luck bestowed upon them, and to pray for continued favor.

Then the mother adds: Ofuda wo osame ni mairimasu

I haven’t seen this line translated correctly anywhere. So let me try and explain. First, an ofuda is a kind of talisman or good luck charm. I’m sure I’ve talked about these before. But even today you can buy them at most shrines and temples. They’re fancy amulets that have been prayed upon and otherwise imbued with special protecting god mojo. They can be silk and brocade or wood and paper or combinations of those.

The line is ofuda wo osame ni mairimasu. All the translations I saw said things like buying an ofuda or dedicate an ofuda. But what happens is these ofuda don’t last forever. You purchase one at the shrine or temple of your choosing, and bring it home. But after a year is up you have to take it BACK to the same shrine or temple and return it. There it will be disposed of properly. Mostly likely burned on a big fire. You are not supposed to, by any means, just toss one into the trash. That’s incredibly unlucky.

Side note: on New Year’s day and those first days of New Year you can find big bonfires called dondo Yaki at the beach or on temple or shrine grounds. These burn all those ofuda, omamori, old daruma dolls, etc. So a lot of people bring their old charms and lucky trinkets here to toss onto the fire where they are prayed upon properly by a priest or monk.

Back to the lyrics. The mother isn’t going to BUY a talisman, she’s going to return one. So the child is at the end of their seventh year more than likely.

To which the monban sings: Iki wa yoi yoi, kaeri wa kowai.

Going is good good or fine fine, or easy, but coming back will be scary.

Okay, where did that come from? Suddenly I have questions. As do other people.

First, it could just mean that since it’s a narrow footpath it’s easy to get there in daylight hours, but after you visit the shrine and return, it’ll be dark and dangerous. Like I mentioned before.

A Second Interpretation – Child of the Gods

The next interpretation is really interesting. I just learned that it was believed that up until the age of seven you are considered a child of god, “kamisama no ko”, thus protected by the gods. But after that you become “nigen no ko”, a human child, and more or less on your own. Another similar explanation was that up until seven you’re not EVEN human yet. It’s not until you’ve reached your seventh birthday that you’re people. And that age was five for boys. Boys become human two years earlier than girls. Or let me rephrase that, girls are gods two years longer than boys.

Maybe he’s saying going is fine, but coming back is scary because after you give the ofuda back to the shrine then the child no longer has the protection of the gods and anything can happen. That’s scary. Is that a threat?

Or because this is a shrine on castle grounds and they really don’t like having riff raff coming in to pray, there are a lot of soldiers around acting as guards. The time you’re allowed to visit is also very strict. So going is easy, but be careful leaving because you have all these hepped up samurai just waiting for someone to break the rules.

Then there’s the theory that the singer of the song isn’t a parent. They’re using the child as a front to get into the castle grounds to do some nefarious business. So sure, go on it, but if you do something illegal you’re going to have a hard time leaving.

That’s still a happier interpretation than the one I’m going to talk about now.

A Darker Theory of the Song

The third speculation is one where you must keep in mind how poor people were back then. Starving was a real and daily threat to great numbers of people. We already know the mother and child don’t live not he castle grounds, so they aren’t well off.

Back in the day there were three ways to make sure your family had enough to eat when all else failed.

1. Boukou / 奉公 which if you look it up means indentured servitude. Yes, you would have those children you couldn’t feed work for a household that was more affluent.

2. Kuchiberashi / 口減らし Cutting down on on the number of mouths to feed. By either practicing infanticide or selling the child outright.

3. Ikenie / 生贄 means a sacrifice, a sacrifice like animal sacrifice or…people? Which is similar to hitobashira. Remember that? (Episode 81: The Tragic Stories of Human Pillars) when a person is sacrificed to the gods in order to prevent some kind of natural disaster or appease disgruntled gods.

An ikenie, or sometimes called a hitomigokuu /人身御供 is more providing something, someone as food for the gods.

All pretty bad choices. But the one that is believed by some to be referred to in this children’s tune is the last one. I read several places that say the mother wants to present her child to the shrine as an offering or sacrifice. The place I read this said it wasn’t uncommon for that to happen either, actually.

The line about going is safe and fine, but coming home is scary is supposedly about that. The mother gives her child to the shrine and must return home all alone on the narrow path.

A Light Idea About the Ending

Speaking of scary, another more light hearted idea is that kowai / “scary” was used to mean tired. You’ll be fine going, but coming back you’ll be tired. That sounds nicer, doesn’t it?

Now where can you hear this song today in daily life? Well, some intersections play it to let you know that you can pass. While the song plays you can cross the street. When it gets to the part where Going is fine, but coming back is scary or dangerous at the end, it means the light is going to change, so hurry up!

Okay, that’s it for today! Thank you all for listening. Patrons who get postcards, recently more and more they’re getting sent back. Like they make it all the way to the States and someone there is Nope and returns them. I have about ten that have come back at the time I’m recording this. I usually wait until the next month and send two along in a letter. Letters seem to arrive at their destinations better, knock on wood.

I am going to try a new method though. I’m going to send all cards to one person (my mom?) and have them send them from there. Hopefully this will work for the cards that aren’t being accepted in European countries, too.

Thank you all for listening and supporting the show. You’re the best, everyone of you.

I’ll talk to you again real soon!

Bye bye

I remember hearing this tune at pedestrian crossings in Japan but I never knew what it was! The game that accompanies Toriyanse sounds like the traditional English game “Oranges and Lemons” which has a similarly disturbing (though less subtle) ending: “here comes a candle to light you to bed, and here comes a chopper to chop off your head!” (With the two children who are “it” bringing their arms down over their victim on the last word of the song). I think London Bridge might be playing in a similar way here in the UK, but I’m more familiar with Oranges and Lemons.

Yeah, Richard remembers it, too. My town is much tinier so I only have vague memories of hearing it in the Big Cities.

It could also be that the child is a boy and that the mother refused to return to the ofuda at his 5th birthday. The boy retains his protection, and the mother is struck with memory loss for her disobedience. It wouldn’t be the first time a god punished a mortal like that (and even for less). The only other reasonable time to return it would be with everyone else, during 7th birthday celebrations. Interesting to think about…

That is interesting to think about. I love that the song is such a mystery and everyone has different ideas about what it means. I’d never considered this one. Thank you for sharing 🙌!