Hey, hey, my name is Thersa Matsuura, author of the Book of Japanese Folklore and podcaster here at Uncanny Japan, where I tell you about all the more obscure nooks and crannies of Japanese culture.

The Five Historical Roads of Japan

In today’s episode, I’ll be taking you on a stroll along the walking routes of Old Edo. There were five main ones, called “go-kaidō,” the five Edo routes, or the five historical roads of Japan.

All five started at the exact same point on the Nihonbashi Bridge in then-Edo, now Tōkyō. Three were shorter and meandered up north. Those were the Koshu Kaidō, Oshu Kaidō, and Nikkō Kaidō.

Today, let’s learn specifically about the two longer ones that led travelers to the old capital of Kyōto, the Tōkaidō and the Nakasendō.

A Journey Back to 1645

Imagine it’s a brisk February, 1645, and you’re standing in a line. Ahead and behind you are all manner of merchants and tradesmen, some with long poles across their shoulders, balancing their wares in the basket on either end.

Others are leading small horses loaded down with packages. There are even men and women in fine kimono, being carried in fancy kago with their own entourages.

As for you, all you have is the bundle on your back. You’re dressed up in your traveling attire. Your suge-gasa straw conical hat is still tightly in place around your chin, but your woven waraji sandals have come loose from the day’s walking and are starting to rub your tabi socks against your skin and form blisters.

You’ll have to retie those once you get a chance.

The Hakone Checkpoint

The dark gate of Hakone Sekisho looms in front of you. There was a commotion a little earlier, and the gossip that came down the line is that the officers caught a woman disguised as a man.

Someone said she was a daimyō’s wife, and they were trying to smuggle her out of the city. You know how notoriously strict this Hakone checkpoint is, and also that they have a prison right here on the premises.

You wonder if you should have taken the other route to the old capital, the Nakasendō. Sure, the Nakasendō takes longer, fifteen to twenty days, where the Tōkaidō takes only about ten to fifteen.

It’s also a more difficult walk. Going through the center of Japan, it’s much more mountainous and cold. But it is supposed to be stunningly beautiful, and not as crowded as the route you’re on now, the Tōkaidō.

Also, not as many rivers.

Traveling Documents and Dreams

The wind kicks up and you tremble a little under your indigo-dyed hikimawashikapa pull-around cape with its fancy bone clasps. Under it you’re nervously gripping your tsukote-gata, that rectangular piece of wood that acts as a passport when traveling.

It has all your vital information, name, age, destination, local government seal. You’re a teacher. A budding poet, actually.

And it’s always been your dream to visit the old capital of Kyōto. You want to see where the tale of Genji took place, walk through the ethereal bamboo groves of Arashiyama, see Kinkaku-ji, the golden pavilion doubled in the pond and glittering in the sunset.

But that’s still another ten-day walk away. Right now, you want to make it through the checkpoint, pay your respects at the Hakone Jinja, and then go soak your aching feet and muscles in the Miyanoshita hot spring.

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Political Strategy

It wasn’t that long ago that the whole country was fragmented into numerous warring states, each one ruled by a powerful daimyō feudal lord, and everyone was fighting each other.

There was so much intrigue and shifting alliances, rebellions, bloodshed, and instability. But then came Tokugawa Ieyasu, the shogun who ended up bringing peace to the country that’s going to last over 250 years.

He did this by implementing all kinds of stuff, some good, some not so good. There were things like emphasizing a strict social order where society is now divided into four distinct classes, samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants.

And imposing the infamous Sakoku policies, which isolated Japan for the most part from all of the outside world. This kept out Christianity, but also new technologies and global developments, for example, medicine.

While the rest of the world had adopted Jenner’s cowpox vaccine and the absolute deadly travesty of smallpox was mitigated, Japan continued to suffer for many, many more years because of this isolation.

The Sankin Kōtai System

Another important thing Ieyasu did was establish a centralized military government in Edo, now Tōkyō, that was able to keep down all those pesky daimyōs and their power-hungry armies.

One way he did it was by something called “sankin kōtai,” which meant that those same daimyō had to spend alternating years in their own provinces and then in Edo.

When the daimyō went back home, though, his family was made to remain in the capital, effectively making them hostages, you know, in case the feudal lords got any bright ideas to rise up against a certain Tokugawa Ieyasu.

This sankin kōtai also made sure the daimyōs never acquired too much wealth, which could also be used to start another rebellion, because every other year they had to travel with all their servants and samurai and baggage along one of the gokaidō, and they had to keep up both residences, one in their home province and one in Edo.

It was all quite expensive.

Road Development and Infrastructure

However, a little bonus to all that pricey traveling was that it stimulated the development of the roads, which was another thing Tokugawa Ieyasu was really keen on.

Using that spot on the Nihonbashi Bridge in the capital of Edo as a starting point, Ieyasu took five rough walking routes and had them refurbished. He made these basically narrow footpaths widened, straighter, and overall nicer.

He made sure they were passable year-round, had some dangerous and steep sections paved for easier travel, and built drainage systems to prevent erosion.

Distance markers were also added every “ri” or 3.9 kilometers, 2.4 miles, so you’d know how far along you were in your journey. Sunbeam trees were planted along the way to provide shade for the weary traveler in the hotter months.

Comparing the Two Main Routes

Of these gokaidō, the two most important ones were Tōkaidō and Nakasendō, both connecting Edo to Kyōto. Tōkaidō was the most popular coastal route.

In some ways it was said to be easier because it was shorter and flatter and the weather was nicer in the winter. The Nakasendō Trail, on the other hand, passed through the middle of the island of Honshu.

It took a little longer because of the mountainous parts, but it was less crowded and it was said to have gorgeous scenery.

Speaking of Nakasendō, these days, sadly, the Tōkaidō, the one I live right next to, has lost almost all of its past glory. But there are still parts of the Nakasendō that can be trekked and retain that romantic flavor of old Edo Japan.

The Staging Post Stations

Another interesting and lively part of the Gokaidō highways were the shukuba, or in English they’re called staging post stations. They were also called shukueki.

These were stops along the way that provided rest, lodging, and support for travelers. You could find restaurants, tea houses, and outdoor food stalls with all sorts of local specialties.

There were stables available for your horses, or other animals if you were traveling with those. You could even change out horses if need be, or rent some.

Shukuba could be raucous places where you could meet people from all over Japan, exchange news and gossip, recipes, trends, customs, and even ghost stories.

Tōkaidō had 53 of these shukuba, and Nakasendō had 69. They were spaced out about an easy day’s walk from one another.

Historical Art and Documentation

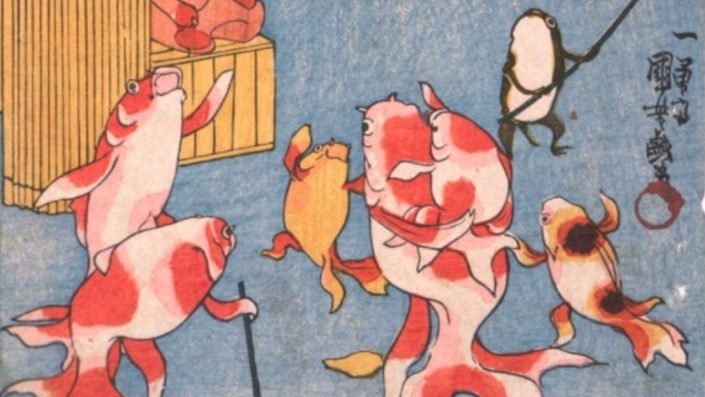

If you want to see what they looked like, check out Utagawa Hiroshige’s collection of prints called “53 Stations of Tōkaidō” (“Tōkaidō Gojusan Sugi”).

He also collaborated with an artist named Keisai Eisen to create a set for Nakasendō. It’s called “Kiso Kaidō,” which is another name for Nakasendō.

Hiroshige produced 47 prints, and Keisai did the rest. Its official name is “Kiso Kaidō Rokujyu-kyu Tsugi” (“The 69 Stations of Kiso Kaidō”), but there are actually 71 images because they added the starting point of Nihonbashi and Nakatsugawa-juku.

I really recommend checking them out. Every single image is a delight, showing beautiful landscapes and the daily life of the travelers. So many quaint and enlightening details.

Security and Checkpoints

But don’t forget, it wasn’t all fun and games. At certain strategic shukuba, you’d have the “sekisho” mentioned earlier, the government-controlled checkpoints to regulate travel, collect taxes, make sure all was on the up and up.

There was a saying back then, it was very popular, “iri depo ni deonna,” or “incoming guns, outgoing women.”

What did it mean? Well, if someone, ahem, feudal lord, was trying to smuggle guns into the capital, or if someone, ahem, feudal lord, was dressing his wife and family up to look like men and trying to sneak them out of the capital, it was a red flag that a revolt was about to happen.

Use the guns to fight and get the family out of harm’s way before it happens. So this is why the Hakone shukuba, or Hakone juku, was particularly strict.

It’s a natural choke point in the Tōkaidō route that’s long been a strategically important pass when moving armies or staving off invasions. Another strategic move by Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The River Challenge

Rivers. Here, let me tell you another saying from that time. “Hakone hachiri wa uma demo kosu ga kosu ni kosaranu oigawa.”

Real quick, hachiri, or eitri, is about 31.4 kilometers, or 19.5 miles. So the proverb means, while it’s possible to pass through the most difficult eitri, Hakone section on a horse, the thing you cannot pass is the Oe river.

Ieyasu was smart. Despite all the revamping and modernizing of the Gokaidō, one thing he steadfastly didn’t do was build bridges over the bigger rivers.

By not having permanent bridges in place, it would be much easier to disrupt the movement of large groups, like invading armies, for example, who got it into their head to try to overthrow the government.

River Porters and Crossing Costs

Instead, once you got to one of the rivers, like the Oigawa, which is like 10 minutes from my house, you have to hire a kawagoe, or river porter.

These were men who literally carried you and your stuff across the shallow parts of the rivers, and they charged by how deep the water came on their bodies. Knee deep was cheaper than waist deep. Chest deep was expensive.

So while the Tōkaidō coastal route usually had better weather and was flatter terrain and shorter, thus easier to travel, and it was more crowded, it’s said that 150 daimyōs used this route when they returned to Edo every other year, while only 30 preferred the Nakasendō.

Some people really didn’t like it because of the river problem. Weather was unpredictable, so if there was a lot of rain and the river was high, the price to hire someone to carry you across also rose and became incredibly expensive.

People would then have to stay for a few days at nearby inns, waiting for the water to recede some so they could finally get on with their journey. But the innkeepers weren’t dummies. They jacked up their prices, too.

Travel Guides and Entertainment

Okay, let’s talk about one more fun thing about these old walking routes. Guide books. They were called meisho-zue, or illustrated guides of famous places, and were sold all over.

They were very popular because they included scenic spots, local temples and shrines, historical sites, different lodgings that were available, local products, specialties, and festivals.

But they weren’t just informative illustrated books. They were also for entertainment. So mixed in with the practical information, you could also find mention of mythical figures and supernatural events and local heroes.

A certain waterfall might be inhabited by a dragon. An out-of-the-way ojizō statue might cure that wart that you have on your face.

Imagine trekking through the forest to get to the Hakone checkpoint and reading about stories of yama-uba, mountain witches, that live there and eat travelers when the mood strikes.

It’s even believed that the tofu kozō yōkai might have been born from one of these booklets, specifically the Edo meisho-zue. The theory is that an enterprising shop owner invented it as an advertising mascot for its brand of tofu, and the little yōkai just kind of took off in popularity.

A Poet’s Journey

Now let me leave you with a poem. A poem you might have composed while on your journey so long ago. But that’s only if you are a reincarnation of Matsuo Bashō, the famous haiku poet, because he also traveled these routes and wrote quite a bit while doing so.

This is one of his poems, and it’s said to express the weariness of traveling for a long time. It was written around 1684.

Toshi kurenu kasa kite waraji hakinagara.

The year ends, still wearing my hat, still in my straw sandals.

Thank you all for listening. Consider becoming a patron if you’d like. I’ll talk to you again in two weeks. Bye bye.