An oiran is not a geisha. Although at first glance they may look alike, one is a more reserved entertainer who is still in existence today. The other is a high courtesan, long disappeared, who wore flamboyant brightly-colored kimono and walked on 20 centimeter high geta.

The Procession/Douchuu (道中)

There’s a procession coming. You along with all your neighbors run to meet it.

First are a handful of dancers and musicians, waving fans or playing handheld drums, wooden and flutes, and ringing bells. They’re all wearing fox masks with long red, blue, or white hair, whiskers of the same colors. The fox, or kitsune, is the god inari and is the patron of the Yoshiwara district and the women who live and work there.

Next come the watchmen, called kanabo hiki (金棒引き), who carry long metal canes with rings fastened on top. They shake the metals rings to both keep time with the music and alert nearby townspeople that the oiran dochu has started. More people gather to watch.

After the kanabo hiki are the tekomai (手古舞). These are women dressed in men’s clothes and hairstyles.

Behind them come the chochin mochi, holding paper lanterns with the name of the top oiran or tayuu painted on it.

Next are the top oiran or courtesan’s servants. They are called kamuro and are young girls with bangs and bob haircuts, dressed in red kimono.

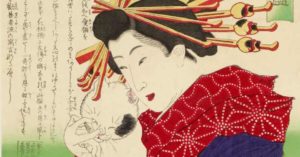

Finally, comes the reason crowds of people are packed on both sides of the street, the oiran or tayuu, the top courtesan herself. She’s absolutely stunning, dressed in layers and layers of brilliantly colored silk kimono, scarlet, gold, turquoise, and silver. Her obi which is called a manaita and tied in the front, is also colorful and intricately embroidered. Her hair is oiled and waxed and adorned with dozens of expensive kanzashi or hair pins and combs made from tortoise shell or boxwood or coral. Framing her face are two silver ornaments with long dangly pieces that sparkle as she walks.

You’ll also notice that she’s taller than anyone else in the procession, wearing a kind of black geta that 20 centimeters or almost 8 inches high. A katakashi no otokoshu stays close beside her, she keeps on hand on his shoulder for support. Behind is the kasa mochi otokoshu carrying a large lacquered umbrella.

For the entire slow procession, when the top courtesan walks she is doing something called a soto hachi monji, where as she steps she twists her ankle, inscribing the figure eight on the ground, then she rocks back, only to step forward again, lightly dragging the bottom of the geta in another figure eight.

What you’re watching is called oiran dochu, the procession of the oiran. So today let’s talk about not the geisha but the oiran, a very high ranking courtesan.

Hey hey, I hope you’re all well. I’ve got no new news to report really, so let’s get on with today’s show.

True story: Every single time I start researching a topic for the show, I find myself going down rabbit holes. So many rabbit holes. To give you an example, for today’s episode I learned the word baidoku (梅毒) in Japanese. Plum poison. What a romantic way to say syphilis. Then that took me to rinbyou (淋病). Rin is a character that means to pour and to drip, while byou is disease. Dripping disease. Any guesses what that it? Final answer? Yeah. Gonorrhea.

Six hours later and I remember what I’m supposed to be reading about in the first place. One of my pet obsessions since I first learned about them, the oiran. What is an oiran?

First, oiran are not geisha. While it wasn’t when I was growing up, I think it’s common knowledge now that geisha (芸者), geiko (芸子) or their apprentices maiko (舞子) are professional entertainers who are trained in various traditional Japanese arts, like dancing, singing, playing several instruments, even learning witty conversation and games to play with their customers. They’re not prostitutes, though.

The old word for prostitute is yuujo (遊女) . The characters for play and woman, or women of pleasure. From the 16th century walled quarters of the city called yuukaku (遊郭) were built. They were deemed the pleasure quarters and it was illegal to do sex work anywhere else. I read somewhere and now can’t find it, but it wasn’t because it was stigmatized , but more to keep areas of the city designated for different things. There was the theater district, the merchant district, uptown areas, poorer neighborhoods, and the yuukaku, or red-light district. The three most well known yuukaku were Shimabara in Kyoto, Shinmachi in Osaka, and Yoshiwara in Edo (now Tokyo). All the yuujo who worked there were classified and licensed.

Of the different classes of yuujo, the oiran refers to very high ranking courtesans with the tayuu (太夫) being the very tippy top. So tippy top, as an example, in 1688, there were 329 registered courtesans in Shimabara (Kyoto) and only 13 tayuu. In Osaka and Yoshiwara there were 2,790 courtesans and only three tayuu.

The word oiran comes from the phrase: oira no tokoro no neesan, the young woman at my place. The kanji characters for oiran are flower and first or leader.

An while, yes, they also engaged in sex work, they were trained in traditional arts similar to the geisha: traditional music, calligraphy, tea ceremony, waka poems, koto, shamisen, flower arrangement, and the strategy game, go. While some of their skills were the same as geisha, some were quite different.

Differences Between Oiran and Geisha

How do you tell a geisha and an oiran apart? Actually it’s quite easy.

The quickest tell is to look at her feet. While both wear geta, the geisha’s are low to the ground and she wears them with white tabi socks. Oiran wear tall geta — to make sure she’s taller than everyone in the oiran dochu procession I described earlier — and she wears them barefoot. Look for the barefeet. That’s an oiran or tayuu.

Also the geisha’s kimono compared to the oiran’s or tayuu’s was while elegant, was still quite modest and subdued in color and design. The oiran’s being more brightly colored with even gold patterns and almost ridiculously layered and very heavy in every season.

And that gorgeous obi tied around their waists? That’s a big difference, too. We’re used to them being tied at the back. That’s how the geisha and normal people wear them. But oiran have them tied to the front in what’s called a maemusubi (前結び)or front knot.

There are several theories to the reason for this. One I read over and over was they did that because the obi were so extravagant and expensive and sometimes gifts from patrons, that they wanted to show them off.

Another big difference is the hairstyle and number of ornaments. Hair pins (kanzashi) and combs (kushi) were also given as gifts from fawning very rich customers so they too were prominently displayed. The oiran or tayuu wore many, many hair ornaments.

So the oiran were kind of the celebrities of their day, popular not just inside the yuukaku, but also outside. If a merchant wanted to spend time with an oiran it would set them back a year’s salary. Also, the higher the class the more say she had in who she saw. So, of course, it was the very upper classes who could afford them. They were even sometimes called keisei, castle topplers, because they were so intelligent and clever and charming that they could steal the hearts of upper class men and basically get them to do whatever they wanted. There are some kabuki plays that have this as their theme.

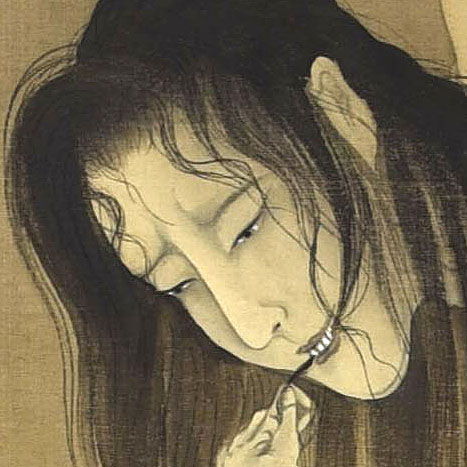

They were popular and known for their beauty and I’ve read it again and again, but they were kind of like the pinup girls of the Edo Era. Quite a few of the bijinga (pictures of beautiful women) ukiyo-e prints in that time were of oiran. For example, Kitagawa Utamaro very often depicted these women in his woodblock prints.

Nowadays, you can find a reenactment of the oiran dochuu once a year in Asakusa, Tokyo as well as other places. There are photography studios where you can pay to have your photo taken wearing some amazing oiran costumes. You get the make up, hair, even your nails and color contact rental.

Sickness and Poverty

Now that’s the good. But even though the oiran and tayuu are quite romanticized here in Japan, too, that’s nowhere near the whole story. While it’s easy to focus on the gorgeous silks and hair ornaments, the fancy makeup and hair, the superstar status and ceremony, this wasn’t exactly the glamorous job it seems.

These really were girls from poor farming or fishing and sometimes low ranking samurai families who were sold into the business. There were men who would travel around collecting them. I read that they were taught a certain way of talking to hide accents that might give away where they came from.

You have to remember how utterly poor many Japanese were. These were families struggling to feed their children. Then some man comes along from the city. One thing I read again and again and it seems like the way parents justified doing this or maybe it was the line he used to convince the parents selling their little girl was a good idea but it was a saying that went something like: By going to Yoshiwara your daughter will eat white rice everyday, wear fine kimono, and sleep on a soft futon every night. These girls were called kamuro and made to wait on the oiran for years until they were ready to start studying and preparing for … work.

If that’s not bad enough, it was very rare these women had her own wealth, no matter how popular they were and how much money they made, it seems they were always in debt. The people who ran the houses where they worked would charge for every little thing. In effect, they had no wealth. The only way to truly escape the life and the yuukaku was to have some extremely rich man “save” (air quotes) her. Even then he had to pay off all her debt before she was allowed to leave.

An orian worked two long shifts all but two days a year. She got New Years and obon off. Oh, and also there was the plum poison. Sexually transmitted diseases were quite common and treatment wasn’t good.

So, that.

I’ll end with a recommendation, if you haven’t seen it already, the 2007 movie Sakuran starring Anna Tsuchiya is really fun. It was the first movie by photographer Mika Ninagawa, so some gorgeous shots and colors. Sheena Ringo does the sound track and she is amazing in everything she does. If you want to get goosebumps right now, go watch Anna Tsuchiya’s oiran douchuu scene on Youtube. It’s when she finally gets made top courtesan and she does the soto hach monji walk.

Thank you so much for listening, please stay safe and well. Patrons, I thank you and adore you.

Credits

Intro and outro music by Julyan Ray Matsuura

I have been sculpting some oirans and cannot find out if there is special meaning to their hair ornaments as they are very specific and all the same.

JoAnne, I, too, am very fascinated with the oiran’s hair ornaments and combs. After reading your comment I poked around a little bit and I think I can find some interesting information on this. As a matter of fact, I think it could be an entire episode. I do remember that they were often given to them by patrons or other higher ranking oiran and were a way to show off one’s rank and how well admired (?), loved (?) they were. Let me do some more research and get back to you. I’m sensing and episode on the topic soon, though. Thank you so much for listening and for asking the great question!