Hello there, I’m Thersa Matsuura and this is Uncanny Japan.

A good portion of choosing topics for the show is all those times I’ve personally stumbled across something while living in Japan and asked myself, what or why or how come?

Why Today’s Show?

If it’s something I don’t see anyone else really talking about then it’s doubly nice, because maybe someone else is asking the same questions and not finding answers either, and this could solve a mystery for both of us. Or perhaps it can provide that nice feeling for someone, when you learn something you never thought you wanted to know, but once you hear it, you’re like, well, isn’t that interesting, I need to tell my Book Club. Okay, that’s actually me. But I really wanted to share this.

Today’s show has been on the back burner for a while now. It started a couple years ago when a writer who writes about Japan, but doesn’t live here, came to visit once and was posting photos on social media. They posted one of a little stone statue by the side of the road and explained to their tens of thousands of followers that it was an ojizo and then went on to talk about ojizo statues protect children and stuff like that.

But it wasn’t an ojizo statue, not exactly anyway. I knew the name of the statue because I’d heard or read it somewhere, but didn’t know anything else about it. So I looked it up, just now. Three or four years later.

Today lets talk about dōsojin.

Intro: frogs…

Hey hey, rainy season and super early typhoon season here. Did I tell you the rice farmer behind my house is going to sell off a big chunk of his land. They’re going to build an entire neighborhood with roads going in and out and houses and people.

It’s even more depressing because all these little frogs will be paved over and my daily sunset behind the rice field is going to now be the back of a someone’s house. Fifteen lots and houses, did I mention people? Right now I only have two neighbors and I think we’re all fine with that.

So that’s got me down. But if there is one tiny ray of light, it’s that I got the news last month and thought that they’d start building right away. I kept my eye on the farmer’s house and noticed he plowed his fields as usual, then he flooded them a few days later. Then a week after that he planted rice seedlings. So house building won’t start until the earliest this fall, I assume.

All these frogs you’re hearing now are real frogs, alive and genki and serenading us for one more season. I’m going to record them throughout the summer and fall. Then I’m going to try and save them all before the trucks roll in. I’m calling it Operation Pom Poko. Just like the movie, it should end well.

Okay, on to today’s show.

Road Side Statues

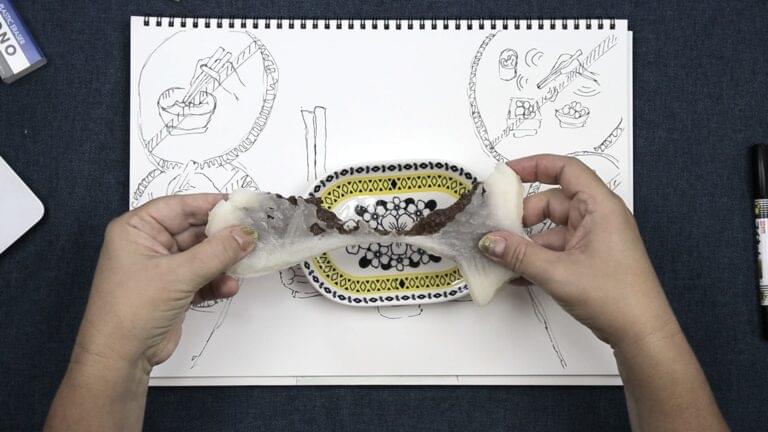

One thing I find infinitely fun about Japan is how you can be walking along almost anywhere and unexpectedly come across some worn statue, usually under a rickety wooden “open on the front” roofed shelter. Often you’ll find a container or two for flowers Sometimes there will be fresh cut carnations, or wild flowers, maybe they’re all dried up, they could be dirty plastic flowers, or the vases could be empty.

You can also find objects people leave by the statue. These can be some lost item someone’s dropped — a single glove, a small toy, a bike key — that a passerby has picked up and placed there to hopefully be found later. Or more likely there’s a humble offering to the deity residing in the stone, a can of tea or coffee, pieces of fruit, a box of unopened Pokki, a five yen coin.

When I come across one, I always stop to look at the statue, say hi, and wonder what it is, why it’s there, how long has it been there, who put it there and — if it’s well cared for — who still tending it? If it looks lonely and abandoned and there are wild flowers nearby I’ll pick some and put them in the little vases, sweep away any gross cobwebs with a stick. If it’s a happy-looking spider, it can stay.

Difference Between Ojizo, Rakan, and Dōsojin

Every statue has its own kami, god or spirit, so they are all unique, but recently I’ve been really interested in the different types. We’ve talked about Ojizo in episode 26 and 27. And I talked about rakan on a patreon post back in November, 2022. Rakan are Arhat statues, actual depictions of the disciples of the Buddha or high level and/or enlightened monks, so they are much more expressive that the calm ojizo we so often see. They can laughing, scowling, whispering into the ear of a nearby statue, or holding a pet cat, enjoying some sake even. Rakan statues have personality. I really like them.

But there’s another category that I’m going to talk about today, and that’s the dōsojin, also called dōsoshin or dōrokujin.

The word dōsojin means “road ancestor deity or god.” They’re not exactly ojizo, but there’s some overlap that we so often see, and even Japanese people sometimes call the dōsojin, ojizo.

But dōsojin are old, really old. A lot of times the poor statues can be so worn you can barely see what’s been carved on them. One scholar I was listening to said they easily date back to the Jomon Era, so this is not only pre Buddhism in Japan but this is before common era.

So there’s one big difference. Ojizo are from the Buddhist tradition, dōsojin are all Shinto. You can think of dōsojin as also the original protector of travelers. After ojizo were introduced later they kind of took over, or helped, I guess. They didn’t completely take over, because dōsojin are still prayed to and there are still festivals celebrating them. More on that in a minute. So you can get an idea of how things start to merge into one another through time.

Early Dōsojin and What they Do

The earliest dōsojin were just curiously shaped or powerful stones thought to contain a kami (or god) and set in special places.

Let’s talk about these special places. Remember when we talked about ikai, the spirit world or other world, or could be underworld. Actually, I just read a interesting definition in Japanese that said “the ikai is the world outside the world that humans are able to perceive”.

Well, these dōsojin were positioned on places that indicated a border or boundary between this world and the ikai, that other side. Like the entrance to a village. Separating that big spooky forest and outside world from the small community within. The world we know is safe, the not easily perceivable one needs to be kept at bay. You can also find dosōjin statues at a crossroads, a fork in the road, on a mountain pass, near bridges, or on corners. Very similar to where yōkai appear, too, come to think of it.

Anyway, they were believed to protect villages, travelers, and even people who were in transitional stages of their life, from evil things and also from disease. Remember small pox, cholera and the measles could just sweep into a town and ravage it. So dōsojin were put up, prayed to and taken care of. Please keep that god of pox away.

When I run across one these days, it’s usually in such a random place, I like to think what boundary was there hundreds upon hundreds of years ago? Did this use to be a crossroads, entrance to a town? What has this little buddy seen?

How to Tell Difference Between Dōsojin and Ojizo

Speaking of running across one. How can you tell if you’ve got yourself an ojizo or a dōsojin? Actually, I really want to learn more about all this statuary. So I’m by no means an expert. But what I have learned is that very often you’ll find the dōsojin are a pair. A male and female figure. Many are very endearing, they’re holding hands or hugging, kissing. Some are a little friskier, engaging in the actual act of getting it on, or you’ll even have the ones that forego the polite facade and you’ll just find an enormous stone phallus under a roof.

All the Things Dōsojin do

Which brings me to the next thing: dōsojin wear a lot of hats and are also tied with fertility, marital harmony and childbirth. Old folk beliefs said and I’m quoting from a Japanese text on various Japanese gods, “male and female reproductive organs were a source of magical power and repelled calamity. In other words, were lucky.” As anyone who has bought those interestingly-shaped keychains sold in gift shops everywhere in Japan can attest. Quoting again, “The phallus was believed to regenerate the spirits of crops, bring about abundant harvests, and encourage vitality that naturally ushers in many descendants.”

So, basically there are different types of these dōsojin statues. A single image, a couple, sometimes just a few words or entire Buddhist sutras carved into a stone, which shows you again the overlap of Shinto and Buddhism. And then there’s the genitalia.

Akita Prefecture has a really awesome-looking dōsojin called Ningyō dosōjin. Ningyo means doll. Instead of the usual small worn down stone statues these are built out of wood or straw and are giagantic.

Let’s talk a little more about the blending that has happened along the years. I already mentioned the ojizo, which came later but adopted similar traits (protection for travelers, taking care of children).

Sae no Kami or Sai no Kami

But another is Sae no Kami or sai no kami. Sae no Kami was talked about in the Kojiki (712). Izanagi no Mikoto despite being told not to, visited his wife in the realm of the dead (Yomi no Kuni), but was chased by a demoness named Yomo-tsushi-kome. In order to stop her, he chucked a stick in her direction. From this stick Sae no Kami was born. Thus becoming the kami that stops evil and bad spirits from crossing from the underworld into this one, a protector of boundaries. Back in the day, Sae no Kami was represented by a large rock placed on those borders between this world and the other. Which sounds a lot like dōsojin. So they started out separate, but kind of represented the same thing, so merged. Sae no Kami is considered a dōsojin.

Batō Kannon — Horse Headed Kannon

My favorite though is probably batō kannon. Where I live now has quite a bit of open land and rice fields and more than a few of the “dōsojin”. But I keep running kannon statues wearing a horses head on top of her own head. They’re very old so sometimes it’s hard to tell. I thought I was going bonkers. Then I found Batō kannon. Batō literally mean horse head.

This deity comes, of course, from China, then further back to Indian culture, but it’s also found in Tibetan Buddhism and that myth is just wild. You have a certain Hayagriva (meaning “having the neck of a horse”) who has a dance battle with the powerful and fierce Rudra. This ends with Hayagriva transforming very tiny, sneaking into Rudra’s, um, backside, transforming once more, this time into a giant, thus exploding Rudra from the inside out. Then when you think it can’t get any better, Rudra — who is somehow still capable of speech — promises to become a protector of the dharma so Hayagriva goes around wearing his body as a suit, and his horse’s head sticking out proudly.

In Japan the story is a little more tame. The Horse head kannon (or Hayagriva) is one of the six avalokitsavaras whose purpose it to save the sentient beings from the six realms of existence. Hayagriva was also worshipped as the guardian deity of horses, and all animals really. Because she/he is the protector of the real of animals.

Nagano Prefecture Nozawa Onsen Fire Festival

There are some neat festivals that still celebrate dōsojin and they seem to take place in early January. The one in Nagano Prefecture at the Nozawa Onsen is epic. It’s a fire festival the main event taking place on January 15th. The day before is spent building a huge makeshift shrine out of wood and straw.

Then on the night of Jan. 15, men aged 25 and 42 (those unlucky years) guard the shrine while chanting “Bring on the fire!” Everyone else participating has flaming bundled reed-torches of various sizes and after some drinks, take this jesting seriously, and start attacking trying to burn that homemade shrine down. It’s brutal. Those 25 and 42-years old put up a good defense, but the whole thing eventually does get set alight around ten pm and burns throughout the night. The next morning in a much calmer mood everyone gathers again to roast mochi rice cakes on the smoldering remains, which ensures a new year of good health.

This fire festival is true to dōsojin’s roots and celebrates childbirth, rids you and yours of evil spirits, and guarantees a peaceful marriage. There are Youtube videos. Look for Nagano at the Nozawa Onsen, fire festival. It’s wild.

Okay, need to get back to writing. Everyone take good care. I’ll talk to you in two weeks which is also exactly the deadline for this book project I’m working on. Wish me luck!

This was an absolutely wonderful article. My husband and I took a clay class last year and he had just read about Dosojin. Even though we are Jewish (and neo-Pagan), not Japanese, he made a male female couple/“Dosojin” for our home altar. They are delightful and I love having a multi-spiritual mash-up. So many religions have overlap with other religions, including the Dosojin it appears!