Hey hey, this is Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan.

Do you remember the last time I talked about a local nanafushi/七不思議? One of those Seven Strange Happenings or Seven Mysterious Occurrences? Well, I looked it up and it was “The Cat and Rat Grave” back in Episode 99. And that was a while ago.

So today I’m going to talk about a new one that’s not only one of the Nanafushigi, but it’s also a quite well known folktale in the Shizuoka area. Further research tells me, it has also made it’s way around the globe in a somewhat different form. More on that and a Story Time in just a bit.

Intro

Hey hey, Terrie here. How is everyone holding up? Spring is in the air here in Shizuoka. I’m looking forward to warmer weather and not getting those electricity bills that more than quadrupled from previous winters. I’m starting to wonder if I should be buying books on how to farm, make my own soap and the intricacies of animal husbandry?

Embarrassing Story of Hadaka Matsuri

On a lighter note, here’s a somewhat embarrassing story that will seque into today’s show. Stick with me. It all comes full circle. When I first moved from Shizuoka to Yaizu, back in the mid nineties, young and fancyfree, I remember being asked if I wanted to go to a “very special festival”. Sure, I said, and grabbed my old Canon AE1 Programable film camera. And boy and was I glad I did.

What I soon learned was that the “very special festival” was an event called Hadaka Matsuri. Matsuri we’ve established before means festival and hadaka for those who aren’t giggling right now, means naked. Naked Festival.

Before you start booking your plane tickets, full disclosure, no one is fully naked. They wear fundoshi, those white cotton loincloths of days gone by. Also, it’s only men who wear them. Women are fully dressed. But even given its misleading name, Hadaka Matsuri is a really cool festival, that I really need to go to again.

I just learned its held for eight days with something different going on the whole time, day and night. There are various purification rituals, one in the ocean; moonlight ceremonies; and something called an Oni Dance which is done late at night, the men now wearing straw skirts and holding paper chochin lanterns, dancing wildly inside the shrine until the divine spirit descends.

Okay, the mildly embarrassing part is that on that fated day, I was kneeling down taking photos. In the foreground a line of men wearing their fundoshi paraded by, while in the background, across the street in an old wooden house, a woman wearing a kimono with her hair all done up, stood looking down at them. I’m concentrating on getting the best shot when I hear a man behind me say to his friend. “Boy, do foreigners like taking photos of butts!”

I couldn’t explain. This was before digital cameras so I couldn’t jump up and show him my awesome composition. I just thought, yup, that’s exactly what it looks like.

Anyway, I very recently realized that the shrine that holds the Hadaka Matsuri is also the shrine where today’s Nanafushigi and folktale originates.

A Note About Names

As with any folktale, you have different variations as the story changes through time. The one I’m going to tell is my distillation of several that I read in Japanese. I’ll mention interesting differences after the tale.

A note on names. With the name of the hero monk, the version on the shrine’s website says his name was Unsui which is a lovely Buddhist name, Cloud Water. But the version in my old book of nanafushigi says his name was Itsukanbou Benzen and I’m going with that one. It’s longer, has a great ring to it, and feels a little more real than the generic Unsui.

Shippeitaro also sometimes goes by Hayataro or Suppetaro or Heibotaro. I stuck to the first one.

The Story of Shippeitaro

Here’s the story of Shippeitaro.

Mukashi mukashi, about 650 years ago, there was a traveling monk named Itsukanbou Benzon and he was trekking all over Japan spreading the teachings of the Buddha.

On this particular summer evening, he was passing through the town of Mitsuke — what is now Iwata City — when he noted the setting sun and decided to stay there for the night. Benzon changed his path and headed to a nearby forest where on top of a high hill he saw a shrine. He’d learn later that this was the Kitano Tenjinja, which later went by the name Yanahime Shrine, and is today called Mitsuke Tenjin Shrine.

By the time Benzon reached the shrine it was well after dark. The place looked to be unattended but he couldn’t be sure. Just in case, not wanting to wake anyone, Benzon quietly removed his tabi shoes, brushed off the dust from the day’s journey, and entered one of the tatami rooms. He then made his way to a corner, curled up, and fell promptly asleep.

Several hours later, though, it must have been around midnight, the sound of voices startled him awake. They were coming from the back of the shrine and were strange in that they were loud and rowdy. Benzon could hear these men drinking and carrying one until they were all very drunk.

Now Benzon wasn’t one to pass judgement and was trying to fall back to sleep, when he heard one of the voices suddenly lower and say:

“Sshh. Don’t let Shippeitaro of Shinshu know about this.”

The other gruff voices replied.

“Yes, absolutely, don’t let Shippeitaro know.”

Now, Benzon’s curiosity was piqued. Who were these men and what were they planning? Whatever it was, it didn’t sound good. The noisy brutes continued their celebration but no matter how hard he tried, Benzon couldn’t make out what it was all about. Finally, out of exhaustion from the day’s journey, he fell back to sleep.

Dawn broke and the monk woke to a quiet and completely empty shrine. Strange. Could it have been a dream? Benzon decided to put the mystery behind him and go on his way. He descended the mountain where there at its foot sprawled the town of Mitsuke. The monk didn’t get far before he stopped. From a nearby house he heard weeping.

Benzon shuffled over and slid open the front door. There in the middle of the room sat a beautiful young lady weeping daintily. All around her, her family sobbed and wailed

“Is everything okay?”

The family startled, seeing this traveling monk suddenly standing at their open front door.

“Excuse me for my intrusion, but I overheard and wondered if I could help. Is someone missing?”

After a moment, the father composed himself and explained that in the town of Mitsuke there was “a very special festival” held every August. During the beginning of the month, out of nowhere, an arrow with white feathers on it would come flying into the village and land on someone’s house.

The home with the arrow had been chosen. This meant they now had fifteen days to prepare because on that fifteenth night the family would have to place their daughter into a white wooden coffin and carry her through the dark forest (lanterns were forbidden), up the mountain to the Shrine. There they would leave her as a sacrifice to the gods. The father reached over and touched the young girl’s sleeve. This morning, he continued. They woke to find the white feathered arrow embedded in their roof.

“That is horrible,” Benzon said. “What if you don’t follow this heartless tradition?”

“Many years ago a family did just that and refused. Afterward, for a year the entire town was tormented. Homes were randomly destroyed and people mysteriously disappeared or were killed.”

“That doesn’t sound like something a god would want to happ—“

It was at the moment that Benzon realized the voices he’d heard the night before were these gods, these Monster Gods, who demanded a human sacrifice. He also remembered what they’d said. “Don’t tell Shippeitaro of Shinshu about this.”

Judging from the father’s story and his own run in with them, these beasts were obviously nothing he could defeat on his own, but if he could find this legendary Shippeitaro that they were so afraid of, then maybe he could bring a stop to this awful tradition.

“I have an idea,” Benzon said. “I know who can help.”

And with that the monk set off in search of this powerful man, Shippeitaro of Shinshu.

It took awhile.

He arrived in Shinshu, now the prefecture of Nagano, and asked far and wide about the legendary hero, until finally, he was directed to a temple called Kouzenji. There he asked the head abbot:

“Is there a monk here who goes by the name of Shippeitaro? I’d like to have a word with him.”

The head monk laughed. “Shippeitaro isn’t a man, it’s my dog. Here!”

From behind the temple appeared a great majestic-looking dog. It was as big as a small cow, well muscled, with bright intelligent eyes, and yet it had a fierce expression on its face. Now Benzon understood the Monster gods’ fear. Surely this animal could defeat them. He explained the situation to the head monk and asked if he could borrow the dog for a little while. The abbot said of course and sent the two off with prayers.

Benzon and Shippeitaro arrived back at Mitsuke in August the following year. It just so happened when they arrived the monk heard another family weeping piteously inside their home. Before he opened the door this time to inquire what was wrong, he took note of the white feathered arrow in their roof.

He introduced himself and told him his plan. This year when it was time to make the sacrifice, instead of the young daughter, Benzon placed Shippeitaro inside the white coffin. He told the dog: “Be quiet for now, but if you see anything suspicious attack it.” And he nailed the coffin shut. Shippeitaro understood his role and didn’t move or make a sound as they carried him up the mountain and left at him in the front of the shrine.

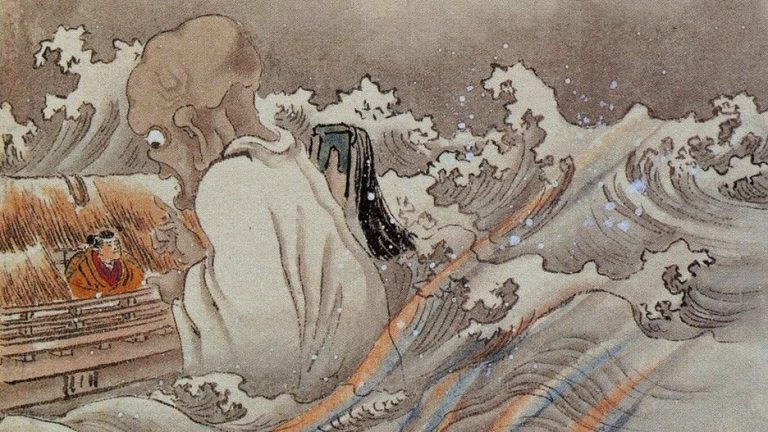

Everyone except Benzon hurried back down the mountain to wait. The monk hid behind a tree and watched. It wasn’t long before the ground shook from the footsteps of the approaching Monster Gods. The first one to appear looked around and sniffed.

“I don’t see Shippeitaro anywhere. It’s safe.”

Next the others appeared and descending upon the white box. They tore off the wooden top ready to devour their sacrifice, only to be greeted by the barking and snarling and biting Shippeitaro. What followed was an epic battle between the dog and the monsters that was heard all throughout the town of Mitsuke and lasted all night until the early light of dawn.

When the townspeople reached the shrine the next day, they found all the monsters in pieces strewn everywhere and the monk kneeling next to Shippeitaro. The brave dog was alive but had been injured badly during the fight. The townspeople cheered their hero and thanked him for the curse he broke. But no amount of celebration could make Shippeitaro stay. The dog wanted to return to his temple in Shinshu, to his master and best friend the head abbot there. So despite pleas for him to stay and rest and eat, Shippeitaro limped off to return home.

There are two endings to this story. Both aren’t happy. In one the dog indeed makes it back to his master and dies in the head monk’s arms. In the other, the dog dies on his way home.

The end.

Shippeitaro’s Gravesite

When I was reading about the nanafushigi and folktale, I found that there is a small shrine that was erected on the site of where Shippeitaro passed away. So last week I drove the two and a half hours into the mountains, out of cell phone reach, and together with my navigator, Richard, we found the shrine. It’s in a very beautiful spot near a small rocky stream. It’s very old, but people are still visiting. There were a couple little presents and coins. I’ll put a photo up on the show notes. For patrons I’m going to put up more Shippeitaro shrine stuff, as well as some video and photos of a 500-year old mountain house where we stayed.

Ever since Shippeitaro’s selfless act of bravery, instead of sacrificing some innocent daughter to the gods, the Mitsuke Shrine and town now have a “very special festival” called Hadaka Matsuri where no one dies and no dogs are hurt. Also, no one is naked, but it’s still fun and exciting.

Versions Outside Japan

Some thoughts. I didn’t realize this tale had been taken out of Japan. But you can find another version of it in Andrew Lang’s Violet Fairy Book (1901) as well as an even older version (1888) which is a German retelling.

Variations of the Bad Guys

In these and other adaptions you’ll find the monsters after destroyed reveal their true selves as cats or monkeys or baboons or rats or tanuki. There’s also the oni or ogres version which sounds on brand.

But let me tell you my favorite. I read a couple accounts in Japanese and they used two words for these bad guys. One was kaibutsu, meaning monster, and the other that I quite liked and had never heard or read before was kaigami. That would be taking the kai from kaibutsu or kaiju or yokai, and adding kami, the character for god. So Monster God. So that’s the one I went with. It adds more mystery to the tale. Instead of the Oh, they were just a bunch of cats.

My Thoughts on the Story

And can we all take a moment to grieve the first girl, poor thing, who was sitting with her crying family waiting for Benzon to return, thinking she’d be saved. But he didn’t show up until a year later.

I did some Google Mapping and the distance between the the town of Mitsuke, no Iwata, and Kozenji is 164 kilometers. Clicking on the the little walky guy tells me that’s a 35 day journey on foot. So I knew there was no way Benzon could make it back in time to save that first girl.

The way the different stories are told in Japanese it was kind of vague. The more child friendly made it seem like he made it back in time, but I found in one version a single line, “By the time, Unsui (this story used Unsui instead of Benzon) returned to the village with Shippeitaro, it was August of the following year.”

So there you have it. Sorry, first girl.

How Long Did the Journey Really Take?

And another thing, I don’t want to nitpick with our hero monk Benzon or Unsui or whatever he goes by, but let’s round up and say it took twice that amount of time to travel. Two months to get to Shinshu/Nagano, and two months to return. Let’s say it also took him two full months of wandering around the city inquiring where Shippeitaro lived. That’s still only six months. But yet it took him a year for the entire round trip journey, almost to the day. I have questions.

Okay, finally, if you ever do make it to Iwata, check out the city’s mascot, it an adorable version of Shippeitaro. I really love that this cool dog’s memory is still being celebrated hundreds of years later.

Thank you for listening, everyone. If you like these kinds of obscure Japanese folktales, for only five dollars a month over on Patreon I translate and put up a new one every month. You can find it be searching for Uncanny Japan and Patreon.

Also, if you like Japanese distilled spirits, Japan Distilled is a really neat podcast that I learn loads from every time I listen.

Stay well, I’ll talk to you again in two weeks.