Story Time: The Human Pillar of Tango

Today I’m going to tell you a story. It’s my translation and then my retelling of a little known tale I found in my dusty collection of folk stories and myth. Remember that day I decided to wander into that used book store I’d never even noticed before. And then after being told to “hurry up, it’s time to go home”, I turned around and there it was all tied together in fraying twine. These stories wanted me to find them. They want to be retold.

So this one is about something you already know about. Do you remember the hitobashira in episode 81? How in older days, in order to appease belligerent or cranky gods, sometimes people were sacrificed, and by sacrificed I mean buried alive — sealed into foundations, pillars, and the walls of tunnels and castles.

All over the country surely there are the powdered outlines of skeletons hidden away, both young and old, still keeping disgruntled gods at bay. Villagers or city folk who gave up their lives (willingly or unwillingly) for some greater benefit (real or imagined).

I ran across today’s story while thumbing through volume 21, the book with stories from Nagasaki and Amakusa. It’s called Tango no Hitobashira or The Human Pillar of Tango. And from the sounds of it, it might very well be true.

Hey hey, how are you? I have another favor, it’s biggly but I think you’re going to like it. My Audio Guy, Rich Pav, and I started a new podcast. We have been working long, long days for at least six months to get it ready and we are both so proud of it. I’ll tell you more details later, but for now, jot down three words, or remember them if you’re one of those fancy people who has a good memory: “Uncanny Robot Podcast”. Come to think of it, there’s only one new word there. Robot. You can search for that after today’s story. Or now if you want, actually. Then come back, of course.

Tango no Hitobashira, The Human Pillar of Tango. Looking around, I believe that this story and a few similar ones, might very well have be the origin of an old Japanese saying or kotowaza/諺. Which we’ll get to at the end of the tale. So get ready to write that down as well, or, if you have that super brain I just talked about, then you can remember it. What was the other thing I asked you to remember? Uncanny Robot Podcast. Very good, thank you!

Okay, there are two things you need to know before I start. First is a hakama. A hakama plays an important role in the story So what IS a hakama? Well, if you’ve ever done the Japanese martial arts, Kendo, like I did in university here for two years, or iado, aikido, kyudo, and even sumo athletes, then you very well know what one is.

I’m suspecting a lot of listeners are already familiar with this garment. But just in case, a hakama is a traditional style of clothing. Imagine those billowy, pleated pants worn by martial artists or on on formal occasions like graduations and weddings, as well as in olden days, you know, pre jeans and khakis.

While women certainly can wear hakama, usually of a different variety, unless doing sports, these cool skirt-like pants are often associated with men’s clothing. They can be regal or working class. In the case of this story, it’s the laborers who are wearing the hakama.

The second thing to kno wis something called a kago. Again, you know what it is, even if you didn’t know its name in Japanese. It’s an old fashioned method of traveling, sometimes called a litter or palanquin in English.

There are different styles of kago, but basically, the traveler usually a woman would sit in this basket-like thing that had a long wooden pole or poles across its top, so it could be carried by a pair, or more, of men. Some kago have sides to protect against rain or wind, some don’t. The one in this story was of the open variety. That’s important.

Okay, I think that’s all you need to know. Let’s begin.

The Story

This all happened in the eighth year of the Tenmon era, in 1539. It was the Sengoku Jidai, or the Warring States Period. As the name suggests, it was a time of near constant civil war and unrest. Be that as it may, during this unruly time in a city on the coast of the Japan Sea, there ruled a daimyo, or a lord, named Tango Morimasa. The specifics of Daimyo Morimasa’s character have been lost to time, but it wouldn’t be too far fetched to assume he was somewhat of a nice person and wanted to make life a little better for the people he ruled over. This assumption being made because of an idea he once had and what became of it.

Tango Morimasa’s bright idea was to reclaim a portion of the seaside in order to create more farms and rice fields. Times being what they were, many families suffered greatly. Fathers, mothers, and children all went to bed hungry, only to wake up hungrier. The daimyo’s plan would ease some of that hardship, so he called for a team of laborers called nimpu to build this beachside agricultural miracle.

The strongest and most skilled workers came from all over to participate in the work. Everyone wanted to be a part of this great vision. It was a very worthy dream. Work began. The men labored tirelessly for long days, weeks, and months. But while progress was slowly made, over and over again their gains were met with loss. Abnormally high tides, rogue waves, freak storms, and mysterious happenings during the night that washed away the previous day’s labor.

Day after backbreaking day, the nimpu continued to show up and to haul more rich soil to repack the land. Only little by little their hopes were dissolving, much like the dike they constructed to hold back the sea. This wouldn’t do, thought the daimyo. The men were all fine, strong fellows. They probably just needed a better supervisor.

Gotango Morimasa approached his most favorite vassals and asked if any would be willing to take on such a difficult project. A very well liked and clever man named Tashiro volunteered, and he excelled.

For a while the reclaimed land began to take shape, and despite the ocean’s attempts to sabotage the construction, they got very close to finishing the project. Only every time they got a day or two away from completion, a part of their work would collapse, get swept away, or drenched with salt water. Something greater than them did not want this task to be completed, and Tashiro was smart enough to realize that.

Then one day he called all the workers together under a certain pine tree that was a favorite gathering spot for the townspeople. No one knew exactly why it was a favorite gathering spot. It was just a place where you could rest and think with a clear head, which is precisely what was needed.

The workers took a seat on the grass under the tree that leaned at an interesting angle and had branches that stretched out like elegant needled fans, offering emerald colored shade for all. It was nice.

Tashiro began, “As you all know, we are very close to finishing our work, and yet every day in one way or another our successes are lost, and we must redo what has been done so many times before.” No argument from his men there.

“It is my belief that the coastal gods don’t like this landfill at all.” Again, not a single disagreement spoken by the men.

“I’ve heard in past times that there is something called a hitobashira.”

Tashiro observed the expressions on the workers faces. Yes, they all knew what becoming a human pillar meant. “This is not something I want to do, but I feel it is our only choice, unless someone has another idea, that is.”

The nimpu laborers exchanged complicated glances, but again no one said a word. “I’ll take that as an agreement. There is no other way. My next question is, do any of you wish to become a hitobashira and see this construction through to the end?”

This time the silence was sharp. Not only did they not speak, but not a single man shifted his position or scratched an itch. Feeling the need to lighten the mood, Tashiro spoke again, this time in a more cheerful tone.

“Well, someone has to do it. Let’s put the decision up to fate.” The beefy, flexing, usually rowdy workers weren’t even breathing at this point.

“Is it true that we are all men who ask our wives and mothers to do our washing and clothes mending?” Hesitant nodding, the workers weren’t sure where he was going with this. “Right, okay, I want everyone to stand up and take off his hakama.”

Now there came some reaction. Take off their pants? But Tashiro explained further.

“Take off your hakama and examine the back. Whomever has some sort of patch sewn there will be the person who is the one chosen by the gods, not me,” he added, “to become the hitobashira.”

The men rose slowly, untied and stepped out of their hakama and then examined them for patches. “Not me,” “or me, I’m good”, “no patches here,” “nothing,” “saved.” Came the gleeful announcements one by one.

“What, no one?” Tashiro asked when the last man had spoken and was getting dressed again. “Well, since this was my idea, I suppose I should check my own, huh?”

Tashiro did so, only to find a large patch had been sewn onto the backside of his garment. “Then I guess the offering will be me then.” With this decision he dismissed the men and returned home.

There his daughter was eager to talk about her upcoming wedding to the oldest son of a wealthy family in a nearby town. It warmed his heart to see her so happy and hopeful. He wished her mother could be there too, but she had passed away several years earlier after a long illness. Tashiro listened to his daughter as he ladled soup into bowls.

Ever since the marriage had been decided for several weeks now, he had been learning to take care of himself. He learned to cook and to clean properly, to wash and mend his own clothes. Tashiro would tell her later about the decision made under the pine tree. For now, though, he wished to hear about friendly sisters in law and gardens filled with irises, peonies and chrysanthemums.

When the day arrived for Tashiro to become the town’s hitobashira, everyone turned out. Everyone except Tashiro’s daughter, who he saw was now living with her new husband and his family over in the next town. After much ceremony and many tears, a comfortable space in the dike was dug out, and Tashiro took his place inside. He closed his eyes.

From that moment, almost as if she knew the exact time, Tashiro’s daughter stopped speaking. Even after the deed was done, the construction continued and finished with no more interruptions. Rice fields were planted and the townspeople were hopeful about the future.

Days went by, weeks, but still Tashiro’s daughter refused to speak. Nothing her new husband or his family or the friendly sisters in law did to comfort her or reason with her worked. She was simply silent.

Finally, after several months, much to her husband’s chagrin, it was decided that she be returned to her home. No matter how lovely she was, this no talking thing did not suit a new bride. So they packed up her stuff, put her in a kago, and with her husband in attendance walking slowly by her side.

She was carried back to her father’s home. Along the way, they traveled down a coastal road and came across the area of reclaimed land where her father had been buried. The rice was beginning to tassel and soon would be ready to harvest. Tashiro’s daughter’s chest ached as she remembered what a great man her father had been.

Suddenly, from a nearby bush, there came the loud cry of a pheasant, Ken, Ken, Ken. It flew up from where it had been hiding with a vigorous flapping of its wings. But just as quickly, the daughter’s husband unshouldered his bow, strung an arrow and shot, killing the bird dead.

The procession stopped. There were excited words exchanged about what a fantastic meal this would make tonight. What a great shot. Tashiro’s daughter had witnessed the whole thing.

She looked at the lifeless bird in her husband’s hand, and on the spot she composed a poem, which she said out loud.

Kiji mo nakuzuba utare majiki yo. If the pheasant hadn’t cried out, it would not have been shot.

Everyone was astounded. What a beautiful and heartfelt poem. For her, though, the realization struck her soul, the pheasant being like her father, good and beautiful, and yet it cried out, as her father did. Both were struck down dead.

There was more excited talk, and right then and there it was decided that she wouldn’t be taken back to her old empty home after all. Since she did speak and she was a fine poet, she could continue to live with her new husband and his family.

To this day it is said that if you walk along the prefectural road in a certain city on the coast of the Japan Sea, you’ll see an old pine tree that leans a funny way and provides cool green shade for all those who wish to sit under it. There you’ll also find an ojizo statue and a stone carved with the characters, monument of the hitobashira.

The end.

From translating this story I learned an old saying. The version in the story is a little more difficult to understand in Japanese, but the more modern, easier version of the saying goes: Kiji mo nakazuba, utaremai /キジも鳴かずば撃たれまい

If the pheasant doesn’t call out, it will not be shot. Or: There is safety in silence.

So that’s something to take away from the story. The opposite of the squeaky wheel gets the grease, I suppose.

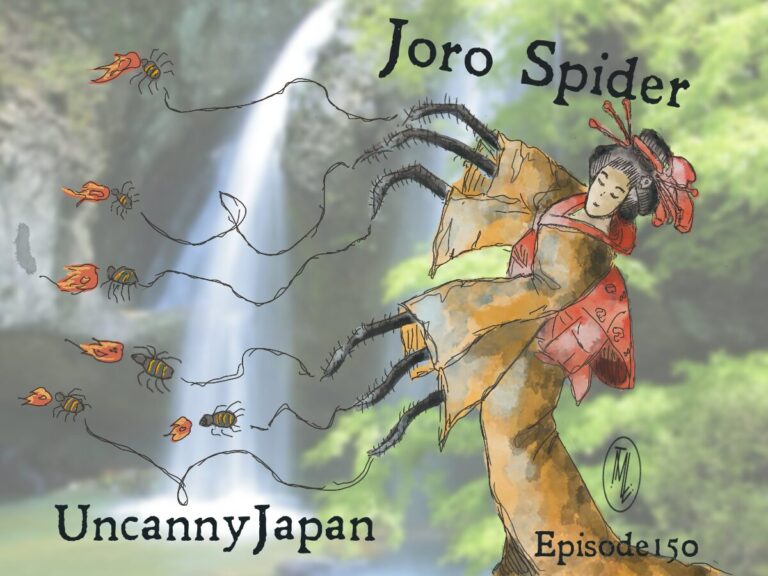

Okay, now I have a little quiz. What was it that I asked you to remember at the beginning of today’s episode? Uncanny Robot Podcast, exactly! So what is it? Well, the catch copy is Surreal AI Generated Stories Read by Humans, but there’s a lot more to it than that. Something about the show is AI generated. The artwork, the music, the videos, as well as the stories. And that’s not as easy as it sounds. Sometimes the AI needs gentle nudging, sometimes a little more stern human wrangling. But all to make the show super fun and entertaining. The stories run the gamut from hilarious, to absurd, to shocking, to creepy, to heartbreaking, to even deeply prescient. You can listen anywhere you usually listen to your podcasts. Or there’s always the website and YouTube. Just search for Uncanny Robot Podcast. And if you like the show, it would be an enormous help if you could subscribe to it or leave a review or just tell a friend. Follow us on social media. Come hang out on the Uncanny Productions Discord. It’s my dream to create a little buzz around the show. We’re both very proud of it. And we think it’s got an audience. We just got to find them. There are three episodes out. The usual pattern of the podcast will go something like two stories, one each generated and read by Richard and myself. The first two shows are exactly like that. But we just made a special Valentine’s Day episode. Like a dystopian hardboiled noir love story. Or Humphrey Bogart dropped into the movie Brazil by Terry Gilliam. It is so much fun.

So that’s Uncanny Robot Podcast. We really think you’re going to get a kick out of it. So if you have a little time, could you please listen? Thank you.

Thank you also for listening to the show today. Everyone take really good care. And I will talk to you again very soon. Bye-bye.

You’ve reached the end of the show. And I just want you to know how much we appreciate you listening and supporting us. Any subscribing, reviewing and gushing to your friends, family, even random strangers really does help keep us going. If you have the means and you want to help a little more and get a little more, we are making extra content over on Patreon. All for only five dollars a month. Or if you like to read horror, you might be interested in my Bram Stoker nominated short story collection, The Carp Faced Boy and Other Tales. Thank you again and I’ll talk to you real soon.

Credits

Intro and outro music by Julyan Ray Matsuura