Introduction

This is Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan.

Have you ever been plucking a delicate piece of maitake mushroom tempura off your plate and suddenly thought to yourself: “Is the reason I can’t make friends in Japan due to me being chopstick challenged? Or maybe it’s worse. Maybe I’m inviting bad luck, evil spirits, and even death to those around me because of my slipshod chopstick technique.”

All right, maybe you haven’t asked yourself these questions, but maybe you should?

About Uncanny Japan

My name is Thersa Matsuura and Uncanny Japan is the podcast about mysterious yōkai, fascinating folktales, and endearing superstitions. Today we’ll learn about how not to ruin your life and horrify your Japanese friends with your chopstick etiquette. I’ll also talk about some godly and decidedly ungodly chopstick lore, and a few thoughts on the harmony of wa.

Thank You to Listeners

I want to thank everyone for ordering The Book of Japanese Folklore and for reviewing it, too. Both those things really help so much. I’m currently writing a fantastical middle grade book, and after that I have regular adult novels – both mythical realism and horror that I want to write, too. Previous book sales and reviews make publishers pay attention. So thank you all so much. I really want to get my next book out there. I think you’ll like it.

Japan: A Country of Rules and Customs

So before I get into the godly and deathly bits of tableware, you may have heard me say before that Japan is a country of countless rules, cultural customs, and very particular ways of doing things. It’s part of the reason (I’ve noticed) that it can be quite difficult to live here. At least that’s my theory after my talks with so many people who have left Japan and perhaps just as many who have stayed but are very bitter and resentful and seemingly unhappy. You see, of those ‘special ways of doing things,’ many are more like secret rules that no one will tell you about but oooh-boy are they important if you want to try and fit in. I’m not saying you can’t make Japanese friends or visit or live here happily if you don’t know them, but the more you know, the smoother life will be. Let’s call that smoothness, wa. Or harmony.

The Concept of Wa (Harmony)

Let me introduce the concept of wa (和) real quick. Here’s my take. Japanese have been living together in close proximity on a relatively narrow island and a bunch of smaller islands for over a thousand years. Add to that the period called Sakoku or Locked Country when Japan for the most part shut itself off from the outside world for 265 years. These are all conditions that encourage a lot of “learning to get along with your neighbors”.

It might be my far-fetched theory, but I believe this has something to do with Japan today being a very high context culture — the definition of high context culture (I just learned and I quote) is one where a lot of information and communication is conveyed through shared understanding rather than being explicitly stated. This goes for the language as well as manners, actions, and social cues. So “wa” is often thought of as a state of balance, unity, or harmony. Everyone knowing how to behave and behaving that way without much needing to constantly remind each other what to do means living a peaceful coexistence. It means Japan’s a nice place to visit.

A Request for Respectful Tourism

I have a favor to ask. This isn’t about you. I know it’s not you, but if you know someone — say a rowdy coworker — who is planning on visiting Japan and wants to chase the Maiko in Kyoto around with their camera; or yell across a store that they found the perfect waifu pillow; or ignore all the signs and fences that tell you not to enter an area and go in there anyway, so they can get a smoldering photo of them sitting on a stone covered in moss that took hundreds of years to grow there — just give that tone deaf neighbor a kindly talking to about wa and harmony and, well, just nice manners. Also, temples and shrines are holy places with centuries old architecture and relics and Japanese people do go there to pray. You wouldn’t believe the stories I’m hearing from Japanese friends about certain tourists. Not you. Your overly zealous roommate.

Okay, now that I’ve worked myself and no doubt you up, please join me in calming down and revisiting our own personal wa. Relaxing, peaceful vibes. Close your eyes. Take a deep breath. Now imagine in the serene void of your mind a pair of chopsticks. Hashi or ohashi, if you’re polite. An innocent pair of ohashi spinning slowly, a magical aura emanating from them. Deceptively simple, aren’t they? Shorter than Chinese and Korean chopsticks. Usually tapered at one end. Sometimes both ends — wait until I tell you what that means. How much trouble can you get into while just trying to slurp some ramen from a bowl, you ask. Well, actually no trouble if you’re loudly slurping noodles. That one’s not a taboo. Slurp away. Back to chopsticks. Believe it or not, there are ways to wreak havoc on yours and maybe others fortune. Here we go.

The History of Chopsticks in Japan

A version of chopsticks was used back in ancient Japan, during the Jomon Era, which began around 14,500 BCE and ended around 300 BCE. They were used, but not for eating. Keep in mind that at that time, bamboo was thought to connect humans to the gods. You can see why this might be believed by how fast and straight bamboo grows and how strong and pliable bamboo is. Anyway, it’s a sacred plant. So a kind of ohashi was made from a long thin piece of bamboo that was bent in the middle. Imagine a u-shape. This is called takeoribashi (竹折箸), “bamboo, bent, chopstick” and was used in very early Shinto rituals. Being a holy plant it was only natural that when making offerings to the spirits and gods, instead of touching things with dirty human hands, these takeoribashi were used.

The Legend of Ohashi Saving a Village

Now let me tell you how a pair of chopsticks saved an entire village. In the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki (8th century) there was written the legend of the Yamato no Orochi — an eight-headed dragon with blood red glowing eyes and a body that spans across mountains and valleys. Very nasty.

Well, in the story, our hero Susanō was walking alongside a river in the middle of nowhere one day when he spotted something floating toward him. What could it be? A pair of chopsticks! Hmm, Susanō thought. That means there must be a village upstream. So he continued on to investigate. And that’s where he met the poor people who were being tormented and eaten alive by the enormous serpent-dragon. Which he thusly disposed of. Although it wasn’t that easy. I’ll do an episode on that story before too long. Something like the Myth Tales Vol. 1 (in episode 132) where we got to be there when Izanagi and Izanami made Japan out of goo. So keep a lookout for that.

Chopsticks as Godly Tools

Back to chopsticks. It’s believed that people started using ohashi for eating about 1,400 years ago in the 7th century. This version (two separate utensils used together, instead of a bent piece of bamboo) were brought over from China. It took some time for them to catch on and the manners and taboos around them have changed quite a bit over time, so let’s fast forward to now.

On one hand chopsticks are godly. They should be used with care as they are the implements that carry food to your mouth, keeping you alive. You’ll also still find connections between them and Shinto.

An example of this are special chopsticks called omihashi (sometimes pronounced onmihashi) written with the honorific “O” (like Ohashi), mi is god or gods and hashi. Basically, sacred chopsticks. On certain occasions, these are given by Shrines to people as talismans or good luck symbols. There’s also iwaibashi, or celebratory chopsticks. These tend to be seen around the New Year or other auspicious times like your baby’s first real meal.

If you ever find yourself with a pair of these lucky utensils, you are allowed to use them, with respect of course. One thing you’ll notice is that both ends are tapered. The symbolism is that chopsticks connect us to the gods. One end, the end we pluck up food with, represents humans and the other end, the gods. A related theory says the word hashi is short for “kami no hashira”, or pillars of the gods. Again, connecting we mere mortals to divine beings. A third idea is that the tapered ends are so we can eat with the gods. While we’re eating with one end, the gods are partaking with the other.

In Japan you’ll find that often people have their own special pair of chopsticks that they use exclusively. These can be used for decades before wearing out or otherwise needing to be changed. So what happens is that over time, a spirit inhabits these chopsticks. Remember in Shinto belief spirits reside in all sorts of things. This isn’t quite a tsukumogami (episode 44, haunted artifacts) because they’d have to be a hundred years old for that to happen, but because of this you’re not supposed to just throw them away. Some shrines even have special ceremonies — ohashi kuyo — where the spirit is removed and they’re disposed of properly. Mostly likely burned. But another method I read about is to wash your old chopsticks in salt water, thank them, wrap them in something, and drop them into the garbage.

Chopstick Etiquette and Taboos

Any way you look at it chopsticks are important symbolic godly instruments. Which makes them persnickety when it comes to usage. Here we have something called kirai bashi / hate chopsticks or imi bashi or kinbashi / forbidden chopsticks. This has to do with etiquette and can run from just being rude to death bringing. Since there are a lot of rule regarding how to use chopsticks — like over 40 — I’ll just go through a handful.

In the don’t be a heathen category you have:

Araibashi. Washing chopsticks. This is when you rinse them off in soup or tea. It’s considered very rude; as is kamibashi, chewing or holding in your mouth or sucking on the ends of your ohashi. That’s very yuck. There’s chigiribashi, using a chopstick in each hand to in effect cut a piece of food. I’m guilty of this on more than one occasion. But never in front of someone else. Next we have yosebashi. This is when you move bowls or saucers around with your chopsticks. Don’t do that. Also don’t mayoibashi, use them to wander over foods, pointing back and forth: Do I want to eat this? Or maybe this? No, I think I’ll eat this. Never ever stab food with chopsticks sashibashi either, or let soup drip from the ends. That’s called namidabashi. Crying chopsticks.

Now a couple of the more heinous faux pas.

First there’s one that seems innocuous enough, but isn’t. Ogamibashi. Praying chopsticks. I’ve actually seen a lot of people do this and didn’t even know it was bad manners until a few days ago. When you hold your hands up like you’re praying in front of your food, but your chopsticks are placed between your thumbs and your index fingers. Sticking out on either side. That’s praying chopsticks and should be avoided.

Tatakibashi. Don’t use your chopsticks to tap on bowls or the table or anything at all. It’s believed this calls akurei, or evil spirits. This is another one I didn’t know about.

The Most Serious Chopstick Taboos

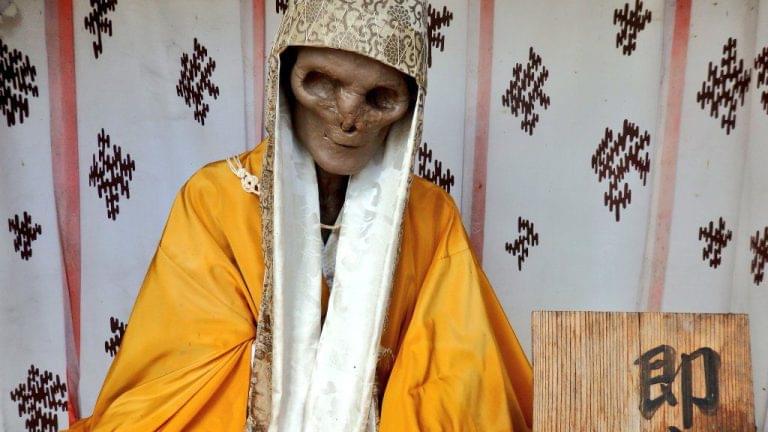

Okay, now for the really bad ones. These have to do with Buddhism and funerals. The first one is tatebashi (standing chopsticks), also called hotokebashi or Buddha’s chopsticks.

After a person dies in Japan, they’re given a symbolic meal. Usually of rice, round mochi rice cakes, and water. Sometimes tea or other things. But it’s the rice we want to talk about today. It’s called Makura Meshi or pillow rice because it’s placed at the head of the deceased. Usually all the items are on a raised tray or altar.

Now if you were giving rice to a living family member you’d fill the bowl but fluff it up. When presenting rice for the dead, the rice is heaped high and packed down. Sometime two full bowls are used and one placed on top of the other and pressed down, before taken off. So you have a fairly high, tightly packed bowl of rice. Then a pair of chopsticks is placed standing upright in the middle of the bowl.

Different characters for the word hashi mean bridge, so this can symbolize a bridge to the Buddha’s paradise or the person’s soul going straight up into heaven. The white rice and other foods providing sustenance for the departed to make the journey.

So you never, ever place your chopsticks stuck in a bowl of rice.

Here’s an example of how off putting this is. A good friend of mine came to work with me at a Japanese restaurant back in university. She was waitressing and on her first day, her first customer was a Japanese man. She went to get him rice and wanting to be nice, she filled his bowl way over the top and packed it all down. So he’d get a lot. She didn’t go as far as to insert chopsticks into it, but just that shape of rice thoroughly freaked him out and he got extremely angry. He called for the owner and refused the rice and the owner had to get him another bowl, filling it the right way. It was quite the big deal at the time. The harmony of the wa broken was broken that day.

This tatebashi is really frowned upon and can be seen as inviting death to someone. At the very least a bad omen.

Then there is hashi watashi. Another seemingly harmless act that is passing a piece of food to someone from your chopstick to theirs. “Hey, try this!” Nope. Never do that.

There’s a point in a Japanese funeral, after the cremation when close friends and relatives gather around and use these very long chopsticks to together pickup bones and move them into the urn. Passing food from one person to another looks a lot like that ceremony and therefore, taboo.

Conclusion

Wew. I’ll stop here. Now I don’t want you to get overly concerned with everything you do or say while visiting Japan. Hey, I still on occasion wear the toilet slippers into a friend’s living room. I like to think of it as a mystery. How should I behave in this situation and why?

Okay, I’ll let you go for now. All my thanks and love to my patrons and to everyone who bought and reviewed The Book of Japanese Folklore and to everyone else, too.

Stay well and take care, I’ll talk to you in two weeks. Bye bye.