An ojizo-sama is here to put aside his own enlightenment in order to save us all from the torments of hell. True story. He is especially partial to children, expectant mothers, firemen, travelers, pilgrims, stillborn, miscarried, and aborted babies. Do you have some kind of pain? He’s here to take that away, too.

The background binaural sounds are a small group of Japanese men and women playing a game of gateball. They’re rooting for each other, taking the piss out of each other, and finally running out of time and losing their games against one another.

Photo by Thersa Matsuura

Hey hey, everyone, this is Terrie and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan’s 26th episode. Two years. Okay, the math is off by a month and two episodes, but I’m close. It was on October 31st 2016 that I put up my first podcast about that incredibly nervous yet excited anticipation you get when you’re about to dive into something new and terrifying. In Japanese it’s called musha burui, the trembling samurai. Here I am a little less musha burui, but still excited about every single show and still chock full of ideas.

I just want to take a second and say how incredibly grateful I am to all of you, the listeners, every single person who has left a review, recommended me to a friend, or reached out on social media to say hey. You are the best. Then there are my patrons, 57 of you. You are not only the best, you are also a very special combination of super heroes and rock stars.

Because of you, I have been able to purchase decent recording equipment and buy lunches and dinners for my audio technician who has worked without complaint to make Uncanny Japan and the Bedtimes Stories sound so amazing, so much better than those early days.

Also, because of my Patrons support I can reveal a little two-year anniversary surprise: I have hired a graphic designer and will be getting an utterly amazing Uncanny Japan logo very, very soon, and that my fine-feathered friends, means merch: t-shirts, stickers, bags, I mean, what else can you put a logo on? I don’t care, I want to put the logo on it. The artist and his wife are also patrons and such wonderful people. If you’d like, check out his work by searching for Travis Pixels.

Now, A hint as to what the logo will look like. Think ojizo statue meets the dark underbelly of Japan. If you don’t know what an ojizo is, you’re in luck, that’s what today’s podcast is about.

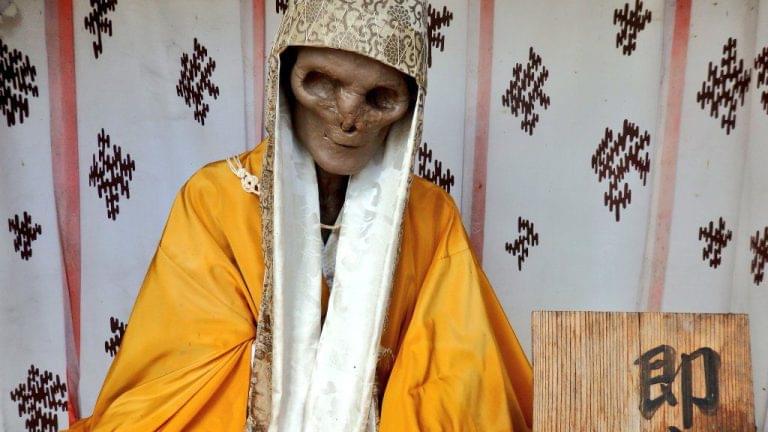

When you come to Japan you will see ojizo statues everywhere; at temples, cemeteries, on roadsides, and in nooks and crannies between buildings. Sometimes you’ll see them with little red knitted hats and bibs, sometimes you’ll see them with a staff in one hand and an odd round thing in the other. There are many different types of ojizo and they all have very different and specific jobs to do, but before I get to that, let me back up.

What is an ojizo? Like Buddhism, ojizo originated in India, moved through China, before arriving in Japan.

The jizo, ojizo to make it more honorific or ojizo-sama to make it even more honorific is a kind of Buddhist deity. He’s thought to be the savior from hell’s torments, the patron of children, expectant mothers, firemen, travelers, pilgrims, stillborn, miscarried and aborted babies. He is also believed to be the protector of all beings caught on one of the six realms on this wheel of life, among other things.

An ojizo is one of the four main Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism. What’s a bodhisattva? A very simplified way to think about a bodhisattva is he or she a kind of buddha, but one who vows to hold back of his or her own enlightenment until every last person has been saved.

I remember a university professor commenting once about this show of compassion makes bodhisattvas even better than buddhas. Buddhas attain enlightenment, pop off the wheel of life and are done with all this. Bodhisattvas stick around to help. They care about us.

It’s written that the jizo acts to save people during the very long Buddha-less age. This is the time between the death of the Shaka Nyorai (who we think of as the first Buddha) and the future Buddha, the miroku nyorai, which is still a ways off. The expected date of the second coming of the Buddha is roughly 5.6 billion years from now.

Okay, let me talk for a second about the characters that make up the name jizo. There are two kanji and together they’re a little bit difficult to translate. Ji (地) is easy, it’s the character for earth, but zo (蔵) can mean storehouse, repository of treasure or womb.

So some translate ojizo as Earth Storehouse, Earth Store, Earth Matrix or Earth Womb, or even Earth Repository. As you can tell, none of those are very cool although I kind of like Womb of the Earth myself. But I think the best is just to call the little guy ojizo. So that’s what I’m going to do.

How do you know you’re looking at an ojizo? Like I said, there are many different types. The story of him has changed and branched out through time.

How long? It’s thought that the ojizo entered japan when Buddhism did in the fifth of sixth century from China through Korea. The oldest known statue is carved out of sandalwood and was a present to the emperor Bidatsu in 577 CE.

You’ll usually find two types in Japan. The first is a more traditional image. He looks like a monk, almost always standing, sometimes sitting, bald, monk’s robes, holding a staff in his right hand, called a shakujou, and a wish-fulfilling jewel, a houju, in his left. Sometimes he won’t have the staff but instead his hand will be making a mudra. A mudra is like a hand sign that has a special meaning. The ojizo’s signs are usually for granting wishes or making someone fearless. Sometimes he’ll be holding a child and or have children standing all around him.

The second is especially popular and unique to Japan. He’s the one with the red cap and bib. Not always but more and more you’ll find him depicted with a cute childish face. This version is very much the protector of children–born, unborn, and sadly those who have died.

These ojizo are here to help protect and save mizuko, the characters here literally meaning water child. These are the miscarried babies, stillborn babies, and aborted babies. Very interesting that this is probably the most common ojizo you’ll find in Japan and yet it’s the newest. The word mizuko is nowhere in Buddhist scriptures. It appeared in Japan in the 1960s, being a way to relieve the suffering of the huge number of women who had to have abortions after WW2. There is so much to say about the mizuko and the ceremonies that surround them, and I think I’ll do an entire podcast on that later. But for now just know this is the most common ojizo you’ll find in Japan.

It’s both fascinating and heartbreaking to come across these little statues adorned in babies attire, often hand knitted caps, bibs, and capes. Sometimes there will be flowers or children’s toys set around the statue. Pinwheels will be stuck into the earth, all clicking in unison. Sometimes there will even be a name sewn onto the bib or a message scrawled on a piece of paper and left. Like I said, heartbreaking.

Something you’ll also see, and I’ve talked about this before on the Hungry Ghost episode, is piles of stacked stones. Why the stacked stones?

This comes from the belief that children who die get stuck on the banks of the river Sai No Kawara, the riverbed of the netherworld. Because they have caused so much grief to their parents and others, they are made to do a kind of penance, which is stacking rocks on the river bank. The story goes that the children stack the stones all day long, and then later horrendous oni swoop down use their great bit iron clubs to smash these piled rocks. The next day the children have to start again. Bereaved parents come and stack rocks in this world, possibly believing they can shorten their child’s suffering or that they’re somehow helping these little limbo children in their own endeavors.

Another type of ojizo you’ll find is one that is thought to heal or alleviate pain when the devotee rubs the statue on the same part of the body that corresponds with their own pain or disease. For example, If you have a sore left shoulder, you’ll rub the left shoulder of the ojizo and pray for relief. Because of this you’ll find these statues usually worn down from thousands upon thousands of hands rubbing their heads, their faces, their joints. It’s all very surreal.

There is so much more. For now consider this a very brief intro into what an ojizo is. By the next podcast, I’ll have a new logo and you’ll see the adorable little spooky ojizo Travis made for us and know a bit about him.

Oh, before I forget, this month’s Bedtime Story over on Patreon is going to be a folktale about an ojizo. It’s called The Sweating Jizo.

Speaking of the next podcast, I think next time I’m going to go into a little more detail about him, the Sweating Ojizo, and the other specialized ones you’ll find in Japan. No more dead babies, I’ll tell you about ojizo that are doused with oil, tied and bound, and headless. Until then, thank you so much for listening, and I will talk to you soon.

(Transcribed using Happy Scribe)

Credits

Intro and outro music by Julyan Ray Matsuura