Hey hey, this is Thersa Matsuura and you’re listening to Uncanny Japan.

A Japanese Cemetery

Have you ever strolled through a Japanese graveyard? I remember in university in the States one day when I was driving some Japanese exchange students somewhere or other and we passed a cemetery. One of them commented that American graveyards weren’t creepy at all. They were like nice parks where you could sit and have an obento with a friend. I asked what Japanese graveyards were like and he said, “Oh, they’re really scary!” As you can imagine my interest was piqued!

If you’ve never seen one, let’s see if I can describe it to you. In general they’re the absolute opposite of sprawling. They aren’t acres of lush green rolling hills dotted with equidistant markers and shade trees. Keeping in mind how valuable and scarce land is in Japan, cemeteries have their gravestones usually built quite close together, sometimes into mountainsides. And the grave markers themselves are a little more complicated.

A hakaishi/tombstone marks the entire family’s plot. Practically everyone is cremated, so ones ashes and quite a bit of bones are placed inside a fancy urn and set inside a hollow part of the stone or marble marker. The main hakaishi is big and rectangular and usually some shade of gray. It has the family’s last name carved on the front and sets atop or near several other blocks, where there’s a space for incense to be burned, water or saké to be poured and left for the ancestors to sip, and vases for flowers or greenery for them to enjoy. They are very neat, clean, and sometimes a little festive. It not uncommon to find gifts of snacks, food, juice, and sake and of course all the pretty flowers decorating a grave. To me they’re not so creepy at all.

Oh, and there’s also a kind of holder by the graves. It keeps these long skinny pieces of wood called sotoba. Sotoba is a deep subject in and of itself, but just know that on them is written the Buddhist name of the deceased among a couple other things. There can be one or several and this is what my friend was talking about when he said Japanese cemeteries were scary. He said, if you go at night, they tend to rattle around suddenly for no reason. Also, all those blocks of stone mean you can’t see what is hiding around you. His words, not mine.

Anyway, this episode isn’t going to be about Japanese cemeteries or funerals, although I’ve been to a few and could do a show on those if you’d like. Today I’m going to talk about a concept I never even considered until I moved here.

In, let’s say North America, you buy a plot of land, pay for it and there you rest forever and ever. In Japan, not so much. Remember what I said about scarcity of land? Well, here aside from the absolutely obscene cost of the funeral itself, you or your family have to pay a temple yearly to upkeep the grave. It’s like rent. So what happens when for some reason or another there is no one left to keep up these payments or no one to continue the various memorial services that should be held at certain times? Or say, what happens if someone dies and they can’t be identified, like in large scale natural disasters, fires, floods, earthquakes, or even suicides where the person’s identity is unknown.

Well, that’s what’s called a muenbotoke. Or “deceased with no connections to the living”. This is actually a really fascinating topic.

Keep listening.

Intro

Hey hey, how are you?

Big Hairy Toe Folk Story

In big hairy toe news, I know, I know. I just love it. It’s a thing now. Mark from “The Folklore Podcast” reached out and let me know about a wonderfully disturbing tale that is very much similar to Cailtlin’s story. Remember Cailtin’s folktale was told her from her grandmother in Alabama. Well, guess what. Let me read to you part of Mark’s message because it made me laugh.

“I thought you might like to know that the “Who’s got my hairy toe” nursery story has been used to abuse and frighten young children in the UK for many years. I certainly remember it from a long time ago personally. A children’s book version came out in 2001 as well.” I followed his link and indeed “Who Took My Hairy Toe” is a children’s book that I wish I could have read to my son back in the day. Awesome. Thank you, Mark for letting me know.

Uncanny Robot Got in to New Jersey Web Fest

One more thing, Sound Man Rich Pav and my other show, Uncanny Robot Podcast, was selected to be a part of the New Jersey Web Fest. It’s an award thingy and they do podcasts, too. Which is exciting. We’re just waiting for them to announce the categories.

Speaking of Uncanny Robot Podcast, we just released our latest episode, “Asteroid Annie and the Mission of the Marsh.” It’s got space heroines, dangerous tentacled aliens, marsh turtles, and a tizzleblast. It took four months to complete and I think it’s pretty hilarious. Each episode is a stand alone story or commentary to one of the stories. So you can start anywhere and not worry about being confused. Well, you might be confused but in an exciting and thrilling way. Asteroid Annie and the Mission of the March is only about twenty minutes long and a hoot. We’ll be putting up the commentary to it soon. Check it out. Uncanny Robot Podcast.

Muenbotoki Meaning

Okay, let me tell you about The Unconnected Dead or Muenbotoke. First, let’s take apart this word: Mu/無 mean nothing, not, or without and En/縁 means affinity, connection, or relation. So no connection, without relations, you get the picture. Botoke is interesting because it is actually hotoke / 仏 a word used for the Buddha or enlightened one, but it has also come to mean a dead person or dead body. Very often with the polite suffix san or sama. Hotoke sama.

So a muenbotoke /無縁仏 is someone who has passed away and they have no shall we say, earthly connections? This could be a person who never had children themselves, or maybe there aren’t any grandchildren to keep up payments or do the proper ceremonies for the grave. Maybe the younger generation just moved away. Or like I mentioned earlier, it could also be an unidentified body. Whose going to pay for that gravestone and plot rental? Whose going to offer prayers?

What are Muenbotoke?

Here’s what is often done, remember I explained what a Japanese cemetery looks like. Well, next time you’re in one, or even go online and look if you’d like, almost always you can find a place off to the side or back of the graveyard that has stacked up a bunch of very old stones.

Personally, I really like these. When I come across any cemetery I make it a point to go and look at them. If my mother-in-law knew this, she’d have a heart attack. Those are spirits who have no one really taking care of them, she might say, they’re disgruntled or sad or angry, she might also say. And they will very likely attach to you and do bad things. Yep. I can hear that, too.

But from and aesthetic point of view, these stones are usually so old and weathered, covered in moss, leaning this way or that, and quite beautiful. But, alas, they are muenbotoke.

The temple has performed the right rituals to soothe their souls and gathered them up and set them aside. Just stacked there. I’ll put photos up on the Uncanny Japan website if you’d like to see.

But here’s a question begging to be asked: So the monks move the stones aside, but what happens to the urns, the ashes and bones? Actually, I don’t know. At least not in most cases, I don’t know.

Isshinji’s Solution to the Problem

But I DO know that I heard about this problem and a brilliant solution years ago and I always wanted to talk about it. It’s been on my episode back burner list for so long, but I jotted the information to look into on a post it note or in some journal somewhere and completely lost it. Thank you search engine. I found it again.

There is a temple in Osaka called Isshinji/一心寺 (One Heart Temple) that is quite modern, actually, and creative in its approach to solving this issue.

Real quick, the temple came about in 1185 when Honen the founder of the Jodo Sect of Buddhism built a little hut so he could practice something called nissokan. Which is basically meditating on the setting sun. Even the Emperor at the time would visit this nice spot to gaze out as the sun set and practice nissokan. Isshinji grew and was lovely and popular. So lovely and popular that it began to collect a bunch of urns with the cremated remains of people inside. How many is a bunch? Well, 50,000 more or less.

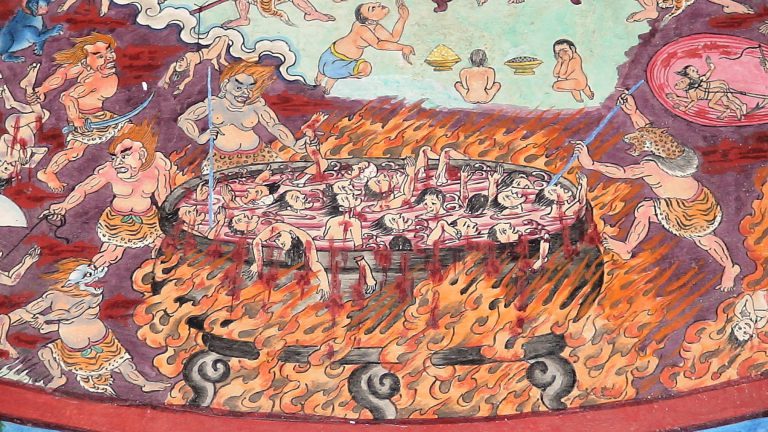

So many that there was no space to put them. In 1887 the head priest commissioned sculpturers to mix these bones and ashes with resin and cast a giant Buddha. Which they did. There were six statues eventually completed and then WW2 happened and the the Osaka Fire Raids destroyed everything. The entire temple complex and the statues. But after the war it was rebuilt and continues this interesting practice of taking muenbotoke and making a Buddhist statue.

These days they make one every ten years. And you don’t have be alone in the world to donate your remains. If you’d like you can give them to the temple and they’ll add you to the … pile? That doesn’t sound right, does it? Oh, they will also accept you’re dead self no matter what your religious affiliation you practiced in life. Which is very nice and inclusive, I must say.

If you go to Isshinji, you can find the statues made thus far in a pair of buildings on the temple grounds called the Nokotsu-do (納骨堂) and the Okotsubutsu-do (お骨佛).

Okotsu Butsu or Bone Buddhas

Okotsu butsu is a word that literally means Bone Buddha. It’s believed that the first Buddha statue made from human remains was a four meter tall Jizo that dates back to the 1700s. It was said to be made by the priest Shingan who crushed up a bunch of bones mixed them with clay and started sculpting. It’s said to still be standing at a temple called Daien-ji in Kanazawa.

Remember how it took 50,000 human remains to make the first statue? Well, now they’re using more. Ten years of donations can get you a lot. For example, the 7th statue that was made after the original six had been destroyed was completed in 1948 and it consist of 220,000 people. Which is like extra sad because of course I’m assuming a lot of those were people killed in the war, not someone voluntarily donating their ashes. In 1957, only 160,000 people were used. And so it goes.

I visited the temples website and noticed an announcement dated January 1st, 2021. Maybe this is due to Covid-19 again making it extra sad, but because the number of urns donated is so great recently, they will only accept small ones now with a diameter of 9 centimeters or less and a height of 11 centimeters or less. And my favorite line in this announcement is “ichi rei ni tsuki ichi tsubo nomi”. One spirit per urn.

Oh, and by donate, I mean there is a fee between 20,000 yen and 50,000 yen, which when you compare to the outrageous cost of funerals here, is nothing at all.

Japanese and Their Ancestors

I find it wonderful and heartening that Japanese are so good at paying respect to their ancestors. I know the generations are changing, but I personally know so many people who offer incense and prayers to their family altars every morning. Little things like if you receive a gift from someone, you might set it on the altar for the ancestors to enjoy first. My father in law used to by lottery tickets and would place them on the altar for any extra good luck juice they might have to offer.

Visiting graves at certain times a year if not more is also very common, too. Like I keep mentioning funerals and acquiring a grave in Japan is the most expensive in the world. So, of course, not everyone can afford that. It’s not super rare to hear of people leaving the urns of their loved ones on trains, in lockers, or just on temple grounds, because of the fees involved.

This is why I really dig what Isshinji is doing. If a family offers their loved one’s cremated remains to be made into one of these large Buddha statues then it’s both enshrining them, giving the surviving family a place to come to pray, and getting the assurance that they’ll be taken care of by the temple through the ages and not hauled to the side of a plot and forgotten.

Okay, that will be all for today, I’ll let you go.

Thank You

I also want to thank Richard my sound, tech, and website guy. He’s still available if you need a podcast editor, sound engineer, and/or all that other rigamarole that comes with launching a podcast. He does the Japan Distilled Podcast which is a fascinating show about all those delicious Japanese alcoholic beverages, their history, how their made. They just launched their own Patreon page if you want to check that out at Japan Distilled Podcast Patreon.

Speaking of Richard. He reminded me to mention the transcripts of the shows are up on the Uncanny Japan website. All the way back to episode 50. We’ll be putting up earlier shows a little at a time. He’s also been spending a lot of hours making sure the subtitles on the Youtube videos aren’t auto generated and actually match what I’m saying.

Thank you everyone for listening, thank you patrons for being the best, and please stay safe and well and I’ll talk to you all in two weeks.