Who are these eccentric street musicians dressed in bright kimono playing drums, bells, clarinet, and saxophone marching down your street? What do they want?

Hey there, I’m Thersa Matsuura and this is Uncanny Japan.

Okay, rewind to 1993. I’d just moved to Small Town, Yaizu after two years studying at University in Shizuoka City, by no means big city. But it was big enough.

Yaizu blew my mind. It was like I’d been hurled into what felt like a more authentic and older Japan. This was shown to me often from how funerals were handled to how laundry was hung out. Note: jeans with holes in the knees were embarrassing enough to warrant a visit from the obaachan brigade. One thing I learned early on is someone is always watching.

But on this one particular day I was all alone in the house, noodling about probably translating and trying to cook something from a Japanese cookbook — no internet back then, so dinner took hours — when I heard some loud music coming from outside.

It was decidedly upbeat, jangly even, and moving closer. Very much like what you’re hearing now. So you know I ran to the door to see what was going on, right?

So what was that raucous music coming from outside? Well, I didn’t know right away because I had no one to ask. But let me describe what I saw.

What Chindon-ya Look Like

Talk about a throwback in time. There, weaving their way slowly up the street was a procession of probably five or six men and women decked out in old fashioned garb and playing various instruments.

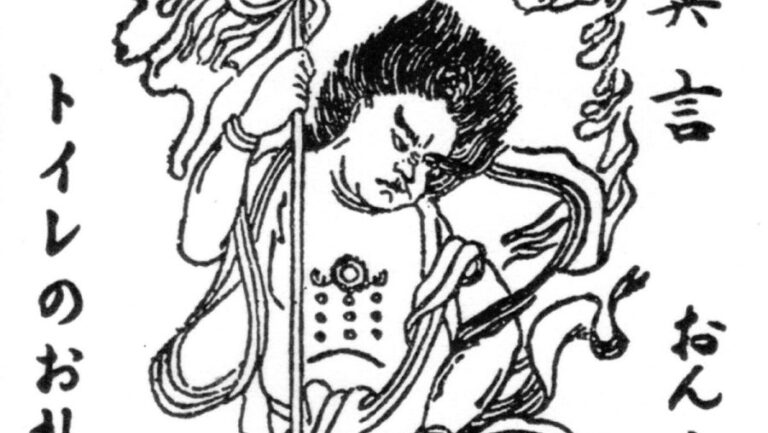

More specifically, the women were dressed in very brightly colored and patterned kimono, their hair oiled and done up with combs and pins. One of the men looked like he’d stepped out of a samurai flick complete with a topknot, chonmage, while the other was dressed like one of the shichi fukujin (七福神), Seven Lucky Gods. He was sporting the poofy red hat and wielding a magic mallet just like Daikokuten.

All of them had an instrument or instruments in the case of the drums. The lady with the drums had two of different sizes, stacked vertically on top of each other, strapped in front of her. There was also a brass plate-looking thing attached that acted like a loud bell. Another woman played a shamisen (三味線) — traditional three-stringed instrument, while the third in line had a clarinet. Our samurai fellow was blowing on a sax and our Lucky God was handing out flyers and wearing a sandwich board.

A sandwich board?

What do Chindon-ya Do?

Yes, what you have here folks is a chindon-ya (チンドン屋) and they are indeed hired to advertise the opening of a new store, a big sale, or some other event. It’s insanity in a very good way.

Chindon-ya is an onomatopoeia, the “chin” being the sound of the bell and the “don” being the drums. While “ya” just indicates that it’s a job or a shop. Like pan-ya/パン屋 (bread store, or better, bakery), omocha-ya/おもちゃ屋 (toy store) or izakaya/居酒屋 (cool Japanese bar).

Who was the First?

But they weren’t always called that. It’s pretty much agreed the idea of chindon-ya began back in 1845, in Osaka. At that time there was a candy maker who sang and made a bunch of noise to attract people to his store. He’d dress up in a straw hat, straw sandals, strap on a belt with these bells all over it, then start hollering about why everyone should buy his candy. His name was Amekasu and it turns out he was so good at what he did, that other shops were like, hey, I’ll pay you, come attract people to my shop, too. And so he did.

After him came a man named Isamikame who would shout “Touzai!/東西!“ Literally East West, but means listen up! Or I kind of imagine it a “Come one come all!” phrase. Anyway, it was from that catch phrase that this way of advertising became known as Touzai-ya. That was out West in the Kansai area.

Then some years later in 1885 one of the Touzai-ya callers relocated to the Tokyo and started his own advertising business called Hirome-ya/広目屋 (Wide Eyes). The same recipe didn’t work though in the Kanto area. One person making a spectacle of theirselves wasn’t attracting customers.

So, being adaptable, he hired more people, gave them all different instruments and had them march through the streets, playing, handing out flyers, and drawing attention to the new shop or special sale or event that way. This worked and these processions were dubbed Hirome-ya — the name of his agency — in the Kanto area. All together they’re known as chindon-ya.

It’s said the years roughly between 1946 and 1960 were the golden age of the chindon-ya with around 2,500 different groups performing all over Japan at the time. Slowly, though, the modern age arrived and by 1985 it seems like there were only about 150 groups left and the performers were all in their sixties or so. In thirty something years here that was the first and last time I saw a live chindon-ya.

Are They Still Around?

But don’t you fret. They are still around, although sometimes more of a hobby or part time gig. And I found that there’s even a contest every April where dozens of chindon-ya gather to perform.

It’s in Toyama City. So if you live there or ever visit, check the city’s event page because for three days in April, under the blooming cherry trees, along the Matsu River around 30 different Chindon groups perform.

What makes up a Chindon-ya Group?

In general, chindon-ya group is usually somewhere between three and seven people, although there can be quite a bit more. Male and female. The first person in the procession is called the hatamochi/旗持ち or hatadori. They carry a flag and hand out flyers for the business. Next is the oyakata/親方, they’ll usually play the chindon drum as well as have a paper umbrella secured to the getup. Third could be shamisen or another drum. I’ve seen people on the banjo, too. After that person comes the wind instruments, a clarinet is nice, so is the saxophone and/or a trumpet.

The word for loud, flashy, or gaudy is hade/派手 and I think the word really defines a chindon-ya. The music, the costumes, the performance is all over the top and boisterous. I personally love the mixing up of east and west — a saxophone with a shamisen — and time — women decked out in kimono with the white make up of a geisha, while next to her is a saxophonist wearing a bowler hat, bow tie, pinstriped suit and a bright green wig. What?

What kind of Music do They Play?

The music, too, can be anything from traditional Japanese tunes to jazz. Although, there is a single song that is representative of the chindon-ya. It was written by a man named Tanaka Houtsumi, who happened to be the leader of a Navy band, Sasebo, in 1902. If that ever comes up in a conversation, now you know. Also, the name of the song is Utsukushiki Tenen/美しき天然.

I watched an interview with a man who has been doing chindon-ya for over fifty years and he said Japanese didn’t even know about triple time until after the war. So when they learned about it, that tempo became popular. The song Utsukushiki Tennen was not only a song basically anyone could play, he said that because it’s not really upbeat, it has this underlying melancholy feeling to it, that Japanese people really like it.

There’s a little more to the chindon-ya. There will be one performer who talks or calls out, touting the shop or event and making otherwise funny jokes or whatever to make the bystanders laugh, grab a flyer, and hopefully visit the store.

Back in my hometown we had a guy in a ratty-looking bunny suit on the corner spinning a sign. That was exact the opposite of making me want to run over and see what he was advertising.

Anyway, I encourage you to go to Youtube and watch some videos, you’ll definitely get a kick out of them. I know it.

This One’s Dedicated to my Father-in-Law

One more thing, before I go, I want to dedicate this episode to my father-in-law. He passed away last month and he really was one of my favorite people. You’ve surely heard about my mother-in-law here. She’s a firecracker and a half and everyone knows it, but no matter what the issue she and I were dealing with, he always took my side. Especially when she was being a little much.

One funny story was when I made an apple pie. I must have been really newly married, like within the first year and I noticed the complete dearth of pies in my city. So I baked one and took it over to my in-laws just assuming they’d love it. Well, my father-in-law gushed about how delicious it was. The best thing he’s ever eaten. While my mother-in-law was like, I’ve been married to you for forty years, you hate cinnamon. Not anymore, he said.

He was so sweet and giving, funny and absolutely selfless. The kind of grandpa that would spend all day constructing a fort in his room out of cardboard to surprise Julyan when he went over to visit. He also had the best smile.

It was a big family with quite a few brothers and sisters, their children, then all the grandkids. All the adults all called him Kochan. We called him jiiji. Grandpa.

Okay, one more short story about how sweet he was: He worked making kamaboko at a tiny place down the street from where we lived. Kamaboko is often translated as fish cakes, but there isn’t much cake about it. Basically white fish all mushed up, re- shaped and steamed. You’ll find it sliced and put in ramen sometimes. Anyway, he worked at the factory from the time he was in elementary school until he retired.

While there for lunch he’d get an obento delivered. With the obento he’d always get a small Japanese wagashi dessert. Those delicate little beauties often made from smooth rice flower and bean paste, shaped into seasonal motifs, like chrysanthemums or autumn leaves. Well, every day for years, before he ate his lunch, he’d wrap that day’s wagashi up and bring it over to me to eat.

So this episode goes up on the 15th, which happens to be his shijukunichi/四十九日, the 49th day after a person’s passing. This is a very important day. It’s when the urn containing the deceased’s ashes is usually interred but also for 49 days it’s believed a person’s spirit wanders. On the shijukunichi the loved one finally moves on and makes it heaven.

Jiiji also loved music. He really loved music, especially the songs from his youth. The song Utsukushiki Tenen was really popular when he was a young man. So with this episode I imagine a nice rollicking chindon-ya dancing and playing jiiji into the the Buddhist paradise, letting everyone know he’s arrived, and everyone excited he’s there. Ojiichans big ol’ smile.

Ojiichan itsumo yasashiku shite kureta arigatou gozaimashita.

Credits

Intro and outro music by Julyan Ray Matsuura

Calm Dreamy Piano by MusicLFiles

Link: https://filmmusic.io/song/8791-calm-dreamy-piano

License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

What a lovely way to honor your father-in-law.

Thank you so much ???? .